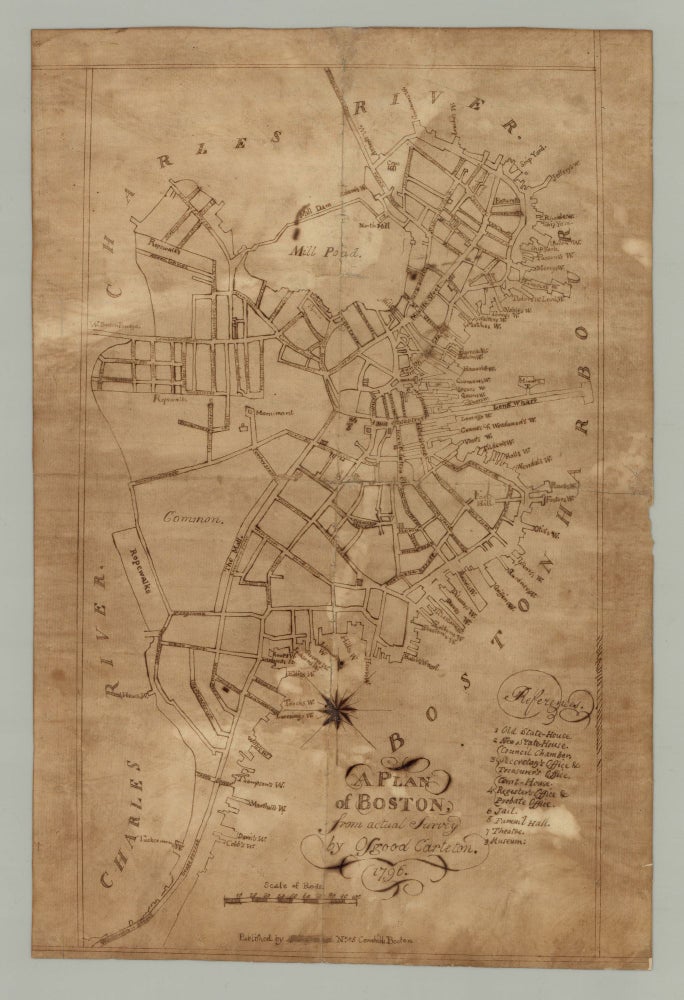

A Plan of Boston, from actual survey by Osgood Carleton. 1796.

[Boston, end 18th century?]. Manuscript in ink on laid paper, 14.25” x 8.375”w at neat line plus margins, uncolored. Apparently produced by reusing a manuscript, as there are several lines of text on the verso, the content unrelated to the plan. CONDITION: Unevenly toned, some smudging of ink, and a few mends and restorations along old folds. Good. An early manuscript plan of Boston, based on Osgood Carleton’s 1796 plan of the city and perhaps rendered by a Boston-area schoolboy or schoolgirl. Carleton’s plan, and this carefully-rendered copy, depicted Boston in greater detail than any map of the town since the American Revolution. The street layout is shown and all streets named, as are the town’s many wharves and other important features such as Fort Hill, the Mill Pond and Boston Common are indicated. Another eight landmarks are numbered and identified by a legend at lower right. The narrowness of Boston Neck, visible at lower left, may come as a surprise to those more familiar with the city in its modern configuration. Commenting on Carleton’s plan, Cobb observes that Carleton’s map is the first detailed map of the town since the Revolutionary era and shows some of the changes that had occurred in the interim: ropewalks had been relocated from Fort Hill to newly made land at the foot of the Common, South Battery had been replaced by Rowes Wharf, and the part of the Town Dock north of Fanueil Hall had been filled in. The first two bridges constructed to provide new connections between the Boston peninsula and the mainland, indicated on [Carleton’s] 1795 plan, are more clearly shown here as the extensions of Cambridge Street and Pine Street. (Cobb, Mapping Boston, p. 189) Carleton’s plan first appeared in 1796 in the second edition of John West’s Boston Directory. The plan was updated and reissued with the Directory almost yearly for the better part of a decade, suggesting that this manuscript was rendered in 1796 or soon after (A later copyist would presumably have had access to updated versions of the plan.) Copied by a local schoolboy/schoolgirl? The map is unsigned, but it seems plausible that it was rendered by a young student in the Boston area. From the 1790s through the 1830s map copying was an important element of American primary education, valued for imparting geographical knowledge and providing excellent practice in drawing and penmanship (Schulten, p. 186). These maps were drawn or embroidered, to some extent by boys but primarily by girls, as the education of the former tended to place a greater emphasis on navigation and surveying than on geography. The source maps were usually from commercially-published atlases, as school geography texts did not begin to proliferate until the late 1810s. The surviving examples of the genre vary wildly: Subject matter includes states, regions, countries, continents and the world; sizes range from a notebook page to large productions on multiple joined sheets; decorative styles range from plain to highly adorned with calligraphic, botanical and/or patriotic ornamentation; and quality of execution ranges from extremely crude—as if dashed off at the last minute to fulfill an assignment—to highly refined. All are, however, interesting as examples of a certain pedagogical model and as windows into the minds of young Americans for many of whom little or no other historical trace remains. In all, an intriguing contemporary manuscript rendering of a scarce and significant post-Revolutionary plan of Boston. REFERENCES: For the printed map, see Krieger and Cobb, Mapping Boston, p. 189, plate 31. For more on Osgood Carleton, see David Bosse, “Osgood Carleton, Mathematical Practitioner of Boston.” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series, vol. 107 (1995), pp. 141-164. For background on schoolboy and schoolgirl maps, see Susan Schulten, “Map Drawing, Graphic Literacy, and Pedagogy in the Early Republic,” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 57 no. 2 (May 2017), pp. 185-220.

Item #3744

Sold