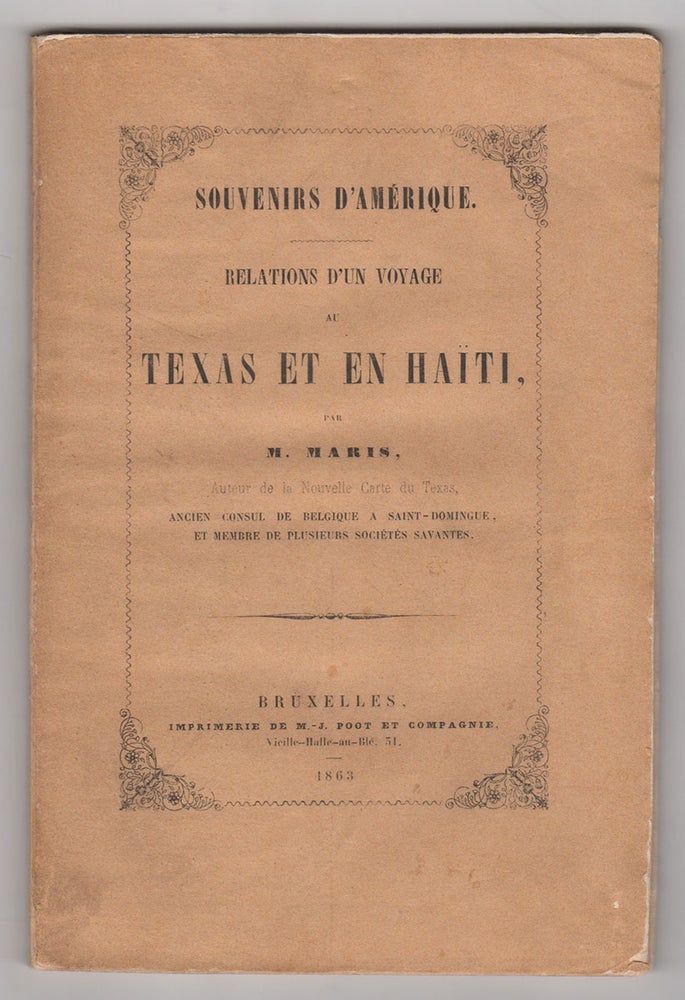

Souvenirs d’Amérique. Relations d’un voyage au Texas et en Haïti.

Bruxelles: Imprimerie de M.-J. Poot et Compagnie, Vielle-Halle-au-Blé, 51., 1863. 8vo, original printed buff wrappers. [5]–63 pp. A fascinating and little-known book by a Belgian traveler, providing a rich narrative of his travels through Texas.. M. Maris, who is said to have been a Belgian Consul to Santo Domingo and is known as a cartographer whose map of Texas was published in Brussels in 1846, recounts his extensive travels in and impressions of Texas, including a visit to Castro’s colony, descriptions of the region's landscapes, flora and fauna, the possibilities for river navigation, the realities of travel and the hardship and danger involved even in everyday life there, as well as his experiences and observations over the course of a sojourn with a nomadic group of Native Americans. “In the hope of rendering myself useful to commerce and industry in general, and above all to immigrants who hope to go to Texas, I felt it right to publish a few pages on that beautiful country, which is so plentiful in resources and whose territory is almost as vast as that of France.” The book is divided into six parts: “Départ d'Anvers pour le Texas, par la Nouvelle-Orléans” (Departure from Antwerp to Texas, via New Orleans); “Courses à travers le pays” (Route through the country); “La grande chasse au Texas” (The great hunting in Texas); “Excursion chez les Indiens” (Excursion among the Indians); “Variétés sur le Texas” (Sketches of Texas); and “Voyage dans l'île d'Haïti” (Voyages in the island of Haiti). Of particular interest is his vivid narrative account of living with a “les Indiens Tankawais” (likely the Tonkawas), which he introduces with a gesture towards the fraught realities of Texas life at the time:

During the course of my traverse through Texas, where due to lack of shelter the traveler is continually under the hard necessity of spending the night under the stars, I was bothered time and again by the many savages one encounters in practically every part of the land, and was even sometimes obliged, for my own protection, to fire several shots.

He nevertheless desired a closer look, and over the next 33 pages Maris’ account moves from romantic descriptions of the variegated grandeur and awe-inspiring silence of the landscape through which he passed, to being abandoned by his Franciscan guide within 500 paces of the Indian camp, to his meeting with a chief and his observations about day to day life, habits, social practices, roles, and structures of the tribe. His impressions upon leaving seem somewhat clouded by the idealized vision of the foreigner, but nevertheless indicate the deep admiration and respect he felt for the people and culture of the tribe:

In living among the Indians, I can sincerely admit to having sometimes regretted belonging to the more civilized class of the human race…I was jealous and envious of their happiness; always so carefree, so gay, in such good health, without physical deformities, free from regret and care for the morrow…

Also of particular note is the following chapter, “Sketches of Texas,” in which Maris gives accounts of the region's landscapes, towns, and cities (including Houston, San Antonio, New Braunfels, Cibolo, and Victoria), governance and potential future relationship to the Union, etc.

The final chapter reports on Maris’ 10 month stay in Haiti. He describes the plant life, crops, climate, culture, governance, cities, etc., of the land, taking into account its history of slavery and noting:

During the course of my long travels throughout Haiti, I was in virtually constant danger of losing my life ; the profound antipathy and hatred that the blacks feel towards the whites is notorious, and is apparently transmitted from father to son from generation to generation. No one among them has forgotten that the Haitians, formerly slaves to the whites, were oppressed by them and that their emancipation came at the cost of so much blood.

Whites being so rare, he describes himself being continually surrounded by crowds of curious children, and he used people’s curiosity to his advantage, in order to find out more about their customs and mores. To close the chapter he recounts some of his more memorable interpersonal interactions, including a conversation with a family patriarch who, showing Maris a small carving he had made of the devil, inspires the following exchange: “I didn’t have the slightest doubt [that it was the devil],” says Maris, “but tell me, Bernard, why did you paint the skin white, since in Europe he is always said to be black?” “The devil, black, monsieur? Impossible!” replies the man: “Here and on the whole island, we firmly believe him to have white skin. Be assured that he does indeed.”

Rare. OCLC records just two non-microform/electronic copies, with no copies recorded in the U.S. However, NUC records four copies, with just one in Texas.

REFERENCES: Howes M288; Eberstadt 332; Sabin 44601.

CONDITION: Good, lightly soiled and creased, first few leaves partially detached, contents clean and attractive.

Item #4131

Sold