The Daily Journal for Ship Ontario from New York for San Francisco.

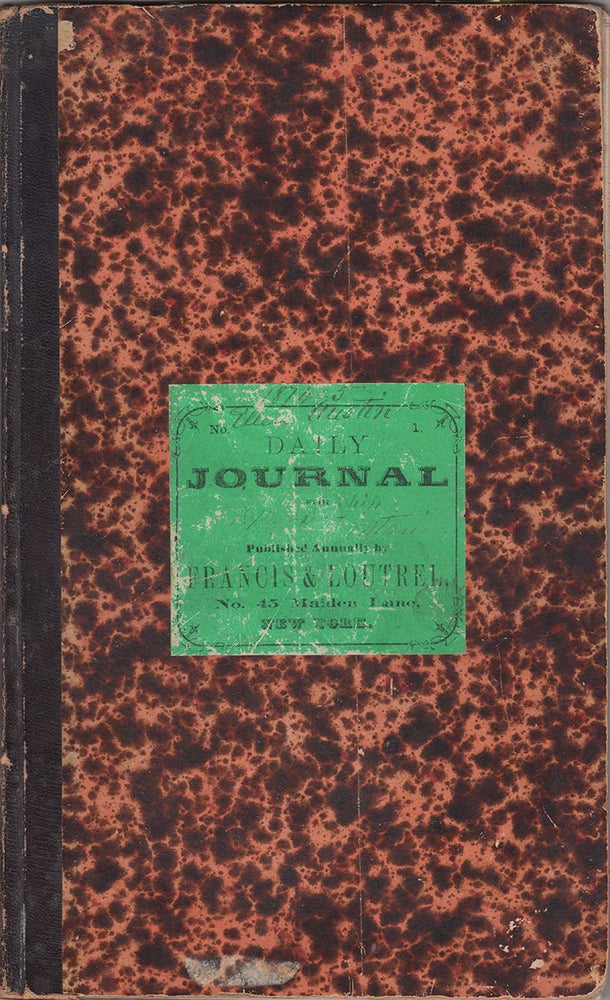

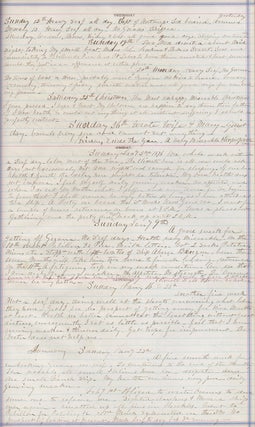

Various locations, from New York to San Francisco: 1872–1876. 4to, half black leather and mottled paper over boards, green title label on front cover. 92 pp. of manuscript. CONDITION: Good. Two manuscript journals in one volume of Maine ship captain Josiah Mitchell (1812?–1876), best known as Captain of the Hornet, famously described by Mark Twain in the Sacramento Daily Union after it burned and sank in 1866. Documented in these sea journals are the two angst-filled final voyages of Captain Josiah Angier Mitchell of Freeport, Maine, October 14, 1872–April 8, 1876, on the vessels Ontario and Ellen Austin. The first voyage, on the Ontario 1872–1873, comes six years after Mitchell’s infamous voyage in the clipper Hornet bound for San Francisco, which caught fire and sank in the Pacific Ocean and was reported in the Sacramento Daily Union by special correspondent, Mark Twain. Upon the arrival in Hawaii of the sole surviving lifeboat (of three) after 43 days at sea, Twain interviewed the survivors there and published the first extensive report of the survival of Captain Mitchell, two passengers, and twelve of his crewmen (“Mark Twain Reports the Hornet Disaster” Gary Scharnhorst). The event constitutes one of the more interesting occurrences in Twain’s own biography; he would address this episode in his My Début as a Literary Person (1900) and would subsequently incorporate it into his Autobiography. The Ontario, built in Newcastle, Maine and owned by Grinnell & Minturn of New York, casts off from the East River in New York City on October 14, 1872, headed for San Francisco—but not before Mitchell is visited by his son: “My only son who had come from Washington to see his father off, on this long voyage—a painful parting for both, such as few know in a lifetime, or understand.” On October 16, the second day of the voyage, Mitchell remarks on his crew: “The crew as a whole, a very inferior set of men but they are here and I must do the best I can with them—Mate don’t seem to have any life in him.” The next day, a man falls overboard, but after an hour in the water they are able to save him—the gentleman being “a good swimmer.” Soon after they depart, Mitchell comments they have too much cargo in the lower hold and worries “the ship will tear herself all to pieces—rolling as she does” on the volatile seas. Consequently, on November 7 they start moving barrels of oil up from the hold; doing so makes the ship easier to navigate. On October 24 Mitchell makes his first reference to his ailing health: “[I] only pray my own health may hold out for I am to be loaded with care all the passage—a thing they [the crew] appear to be entirely destitute of—and utterly unable to relieve me from.” From early on in the voyage, Mitchell and co. are plagued by poor winds (what he refers to as “tedious calms”); he writes, “[i]n all my voyages have never been so long in getting to this Lat + Long—nor did I even try harder for a passage.” As early as November 3, he relates, “I am getting out of all patience.” On November 14 the Ontario is “but little more than halfway to the equator.” Mitchell expects to be making 200 miles a day but is averaging about fifty; this begins to weigh upon him: “I wonder not that so many ship masters are driven to insanity or suicide.” By the 22nd his crew has “taken from below about 100 tons” from the lower hold. On December 1 they finally cross the Equator, watching for St. Paul’s Isles. Mitchell remarks this crossing has taken longer than any previous voyage in his life. Displeased with his crew, he frequently writes that he “suffer[s] for companionship—for someone to talk with.” The next day he makes his first mention of the Chronometer erring. Receiving strong winds on December 6, he remarks, “[w]ould that I could hold a wind like this for 50 days to come to make up for our bad luck.” On the 19th, Mitchell reports that there are “Barnacles thick and growing large” on the ship; the next day all hands are employed to scrape them off. On the 30th he thinks of his beloved son: “you are thinking of me as being off the Cape I know—would that I were.” On January 22, 1873, he writes “[w]hat a fool I was to undertake this voyage—with such officers I never desire to go to sea again.” By February 26 they are south of Monterey, California; his final entry on the Ontario is dated March 31, 1873. On July 28, 1874, Mitchell is now aboard the Ellen Austin from New York for San Francisco, built in Maine in 1854. He leaves the East River, New York with officers and crew totaling 32 souls. He writes that he has “never seen a ship that appears to have had so little attention”; the “ship wants a complete overhauling but the mate is utterly incompetent to do it.” Again, Mitchell is plagued by poor winds; on August 10 he laments, “O for a breeze.” He is also desperately lonely once again: “Why could not Mr Sloan have been willing that a daughter should accompany me on such a long voyage?” On each Sunday he longs to see his family and remarks that “going to sea would not be so bad after all” if “a body could go home on Sundays.” After passing the Equator, they reach the isle of Fernando de Noronha by the night of September 3. He resolves on September 10th, “I’ll make a different ship of her before the voyage is over.” By October 8 they have passed Cape Horn. December 12 is the final entry from 1874. The next entry is dated August 1, 1875, 8 months later; “now lying in the stream at San Francisco, full crew on board, consisting of 17 able seamen, 3 ordinarys + 2 boys, with 3 mates, carpenter, cook + steward—28 souls beside myself. Ready for a voyage to Callao + Guano ports or Islands of Perce and from thence to London.” The Ellen Austin has been lying in this port since December 12, 1874, awaiting business affairs. On August 2, they set out to sea. By now Mitchell’s health has significantly deteriorated, and he ominously remarks that he should not be undertaking such a “long perplexing and hard voyage”: “I am weak + more miserable + feeble than is known to any but myself. I know for my family’s sake, my own, and for all interested in the voyage, it is really my duty to leave.” Once again his voyage is freighted with misfortune: poor winds, ceaseless rain, and poor company. On September 3, they pass the Galapagos Islands but are a week behind schedule as they make way for Callao. These difficulties greatly affect Mitchell’s mental health, leading him to remark, “[I] am nearly crazy”; and, more despairingly, “[w]hat a life to lead for 50 years—and yet obliged to follow it.” “Nervous, uneasy, crass & irritable can’t content myself five minutes in a place I’m getting just like a child.” On October 18, they reach Callao and spend 8 days there. Leaving here, and now on their way to Huanillos to load a cargo of guano, he writes, “[g]lad to put to sea again to get away from all the annoyances of authorities, runners...beggars + sailors infesting such a port.” On November 26 Mitchell arrives in Huanillos, a small seaside village in Chile and large source of guano in the 19th century. The creation of the new village of Huanillos followed the Peruvian government’s approval of the extraction of guano in 1874, just a year prior to Mitchell’s visit. After a few days of business here Mitchell and co. depart on November 30 and make way for Pavillon de Pica off the Peruvian coast. Mitchell writes that they will spend 8 to 9 months in Pavillon de Pica, where he also encounters Italian and French vessels. On December 11, he reports they have loaded some 160 tons of guano per day over the past week. Two men desert on December 19, and on the 26th he reports that his “bowels are very sore and so can’t eat anything.” On January 9, 1876, he writes, “I begin to fear I shall never be any better.” On February 1st, he writes the owners of the ship “to send someone to relieve me,” but he never hears back from them. On March 18 two of his men drown in a “heavy rolling sea.” Near the end of the journal he meets with the Governor and receives 20 extra men for loading guano; he is also in contact with an agent of an Anglo-Peruvian Bank. In his penultimate entry on April 4 he writes, “[h]ealth failing most decidedly”; and in his final entry from April 8, he relates he has received “no letters” from the ship owners, which is a “great disappointment”; he “fully expected someone to take the ship it’s high time & was away if I expect to reach home alive.” Enduring the hardships of life at sea until the end, Mitchell died within months of this final entry. Making for one of the most fascinating and storied oceanic tales, 5 years later in 1881 the same Ellen Austin—captained now by A.J. Griffin—was sailing a London-New York route and encountered an abandoned schooner drifting just north of the Sargasso Sea (“Ellen Austin The Mystery Explored”). After two days of observing the derelict ship—in case it was a trap—Griffin’s men boarded the ship and, upon inspection, declared the vessel intact but curiously found no indications of violence or of a crew. Some of Captain Griffin’s men sailed the abandoned vessel in tandem with the Ellen Austin, headed for New York; however, after several days the two ships were separated by a tremendous sea storm. The ship was never seen again. The last two sea journals of Josiah Mitchell, captain and survivor of the burned and sunken ship Hornet, poignantly recording the additional travails he suffered as both his career at sea and his life came to a close. REFERENCES: “Ellen Austin The Mystery Explored” at Bermuda Attractions online.

Item #4203

Sold