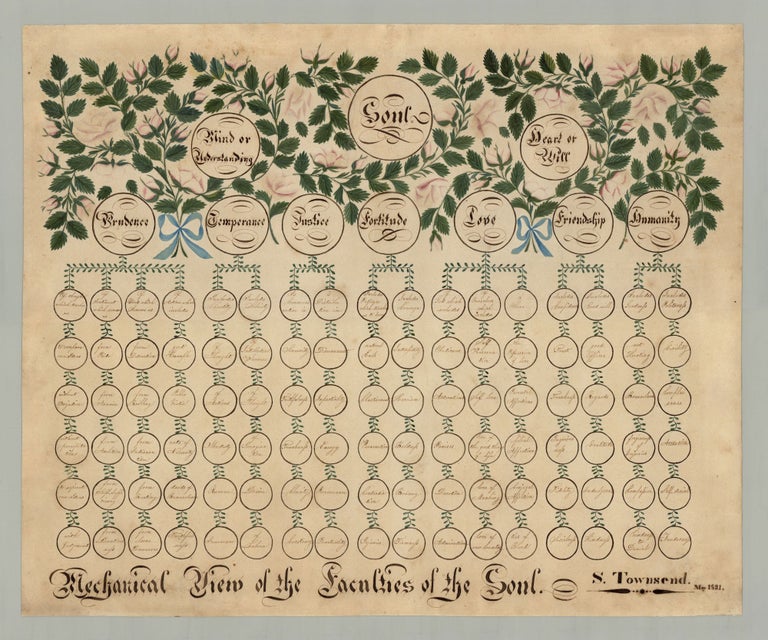

Mechanical View of the Faculties of the Soul.

[Reading, Vermont, May, 1831]. Manuscript chart, 19” x 23” (sheet size); ink and watercolor on wove paper. CONDITION: Good, expertly repaired 5” tear into top center, similarly repaired 1.5” tear into bottom center, occasional paper pulp reinforcement to edges on verso. A beautiful and fascinating work by a Vermont schoolgirl based on an engraved chart for use in a moral “game” devised by French educational author Abbé Gaultier in the eighteenth century. Taking a form similar to that of a genealogical table, the chart consists of a series of circles at the top representing “Soul,” “Mind or Understanding,” “Heart or Will” and seven moral principles, including Prudence, Temperance, Justice, Fortitude, Love, Friendship and Humanity. These are surrounded by elegantly curling rose branches held together by two blue ribbons. Arranged in columns beneath each of the seven principles are circles inscribed with characteristics pertaining to the associated principle. Green vines connect the circles in each column. The title appears at the bottom, beside which Townsend has signed and dated the piece. The engraving upon which this watercolor is based appears in Gaultier’s A Rational and Moral Game; or, A method to accustom young people to reflect on the most essential truths of morality (first published in London in 1780). Gaultier believed that children learned more readily when amused and he advised the teacher to:

carefully remember that he is playing, while teaching; that the magisterial tone, menaces, and reprimands, are incompatible with the idea of this game; and that he has gained his point, when he has once instilled into the minds of children the desire of learning, by a certain hope of amusement.

The game—if that’s the right term—consisted of asking students a series of questions which they were to answer—at least in part—by consulting the Mechanical View. In “merely introducing a little novelty into the pupil-teacher dialogue, in the Rational and Moral Game Gaultier encouraged children to think for themselves and learn to exercise judgement, reflecting a gradual move to more creative teaching and a greater sense of interactive learning” (Shefrin, p. 254).

While it seems likely that Townsend and her fellow students were instructed with Gaultier’s moral game, in her watercolor his table takes on additional life and purpose, here serving as an exercise in penmanship and design. Interestingly, the content of Townsend’s version differs from that in the one example of the engraving that we have seen. Gaultier’s columns of characteristics are of varying length, whereas Townsend’s all consist of six circles. In other words, her table includes characteristics not found in Gaultier’s. For instance, in the right column under Temperance in the engraving the top circle reads “Sobriety” and is followed by “of intellectual pleasure” and “of pleasure or sense.” In the watercolor, Townsend has added three circles to this column reading “of imagination,” “desire,” and “of labour.” In all she has added some twenty-four circles to the composition and also varied Gaultier’s arrangement here and there.

Whether these differences were her own innovations, those of someone else at her school, or based on a different version of the engraving than the one we have seen is unclear. However, it is tempting to think of this as an example of Townsend thinking for herself. In any case, the graphic appeal of the engraving was apparently not lost on American academies of the day. Another (far less satisfying) example of a schoolgirl Mechanical View is owned by the Litchfield [Connecticut] Historical Society. Although far rarer than decorative schoolgirl maps, other examples of watercolors based on Abbé’s engraving probably exist.

Susanna Townsend (1813-1879) was born in Reading, Vermont, the daughter of William Townsend and Susannah Townsend, née Smith. She became a schoolteacher and also served as the Reading town librarian. William Townsend fathered twenty children by two different wives, several of whom became teachers. Susanna’s brother William Smith Townsend (1814-1864) was a writing and singing master and another brother, Dennis Townsend (b. 1817), was a teacher who invented and marketed a folding globe. The Townsends were among the earliest settlers of Reading. “They were...imbued with Puritanical habits and opinions and early turned their attention to education and religion. They were among those who organized the first church in town, and built a log meeting house and parsonage” (Davis, p. 296).

Aloisius Edouard Camille Gaultier (1746?-1818), generally known as Abbé Gaultier, was a French priest and educational reformer. During the French Revolution, Gaultier fled to London where he established a school for the children of French émigrés and published a number of educational games for children, in both French and English, designed to teach history, geography, morals, grammar, reading, and foreign languages.

A manuscript map of Africa by Susanna Townsend, also dated 1831, is held by the Leventhal Center at the Boston Public Library.

A beautiful and compelling example of schoolgirl art, reflecting the influence of Abbé Gaultier on education in early nineteenth century America.

REFERENCES: Shefrin, Jill. “Make it a Pleasure and Not a Task”: Educational Games for Children in Georgian England in The Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. 60, No. 2 (Winter 1999), pp. 253–254; Davis, Gilbert Asa. History of Reading, Vermont, vol. 2 (Windsor?, Vt., 1903), p. 296

Item #7099

Sold