Floyd’s Flowers or Duty and Beauty for Colored Children: Being One Hundred Short Stories Gleaned from the Storehouse of Human Knowledge and Experience.

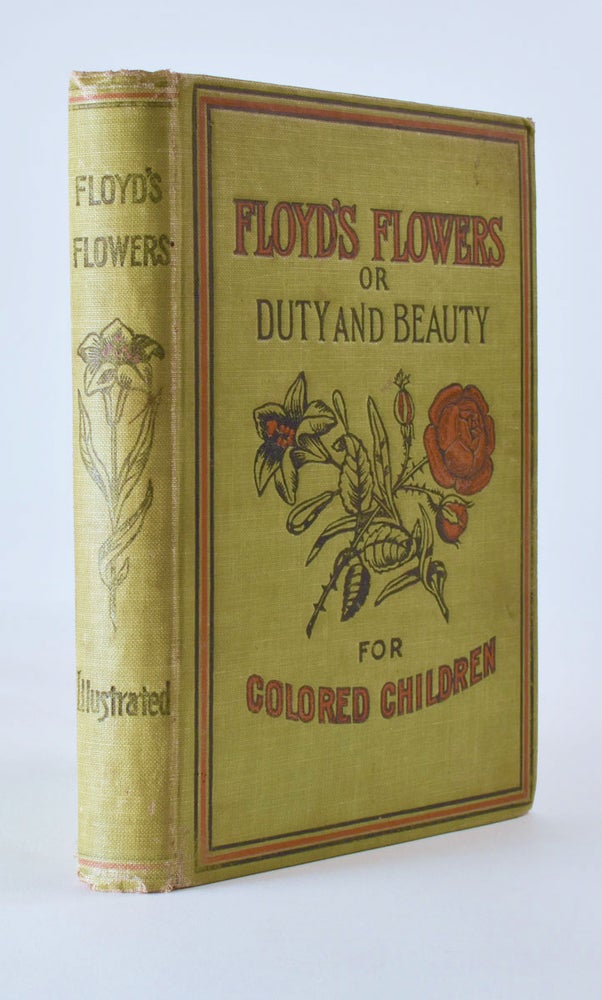

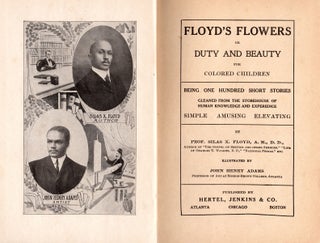

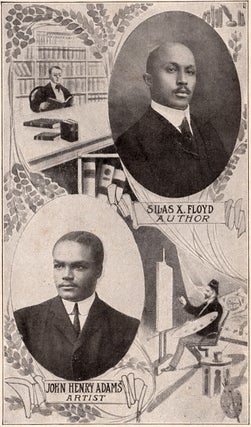

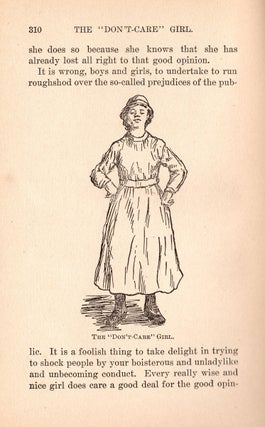

Atlanta: Hertel, Jenkins & Co., 1905. 8vo (8” x 5.75”), original pictorial green cloth printed in red and black over boards. Frontis., 326 pp., 80 b&w illus. throughout. CONDITION: Cover good +, extremities worn and corners bumped, chips to lower spine, inner hinges cracked; contents very good. First edition of this important collection of conduct and morality tales for African American children, written by a leading member of the “emancipation generation” and illustrated by an artist who would go on to work extensively with W. E. B. DuBois. Advertised as “the only book ever published for negro children,” Floyd’s Flowers deliberately avoided discussion of the “sufferings which are inflicted on the colored people in this country.” Instead, its short, uplifting tales aimed to provide models of exemplary behavior and high morality, and in doing so to “elevate” young minds and fill “many hearts” with “high and holy aspirations.” John Henry Adams’s black and white illustrations are charming and direct, and, as the Afro-American in Baltimore observed, “One of the things we like about the book is that the illustrations will serve to inculcate in the young folks the idea that colored people can get their pictures in books as well as white children, and therefore stimulate race pride at a time when it will do most good.” Stories cover examples of what not to be (“The ‘Don’t-Care’ Girl” and “The Rowdy Boy”); principles for how—or how not—to behave (“Principles for Little Gentleman,” “Going with the Crowd,” and “The Road to Success”); and role models to emulate (“Frederick Douglass,” “A Hero in Black”). Offering a nonviolent, self-contained strategy for uplifting African Americans during “the nadir” of racist backlash against Reconstruction (Morgan), Floyd’s Flowers was immensely popular, and was even used as a textbook in some schools. In a chapter headed “The Future of the Negro,” Floyd explains his approach: I believe that the less you think about the troubles of the race and the less you talk about them and the more time you spend in hard and honest work, believing in God and trusting him for the future, the better it will be for all concerned.…I know that we are discriminated against in many ways…the right to vote is being taken away from us in nearly all the Southern states. Lynchings are on the increase. Not only our men but our women also are being burned at the stake. What shall we do? There are those who say that we must strike back—use fire and torch and sword and shotgun ourselves. But I tell you plainly that we cannot afford to do that. The white people have all the courts, all the railroads, all the newspapers, all the telegraph wires, all the arms and ammunition and double the men that we have.…We cannot afford to lose our decency, our self-respect, our character.…In spite of prejudice; in spite of proscription; in spite of nameless insults and injuries, we cannot as a race, afford to do wrong. But we can afford to be patient. God is not dead. Silas Floyd (1869–1923), whose parents were born into slavery, was an educator, preacher, journalist, and civic leader from Augusta, Georgia. After graduating from Atlanta University in 1891, alongside actress Adrienne McNeil Herndon and educator Helena Maud Brown Cobb, he co-founded the Negro Press Association of Georgia and occupied several roles in the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools. Heavily influenced by Booker T. Washington, Floyd promoted educational and moral improvement for African Americans over direct political engagement. John Henry Adams (1878–1948), also born to formerly enslaved parents, was still a young artist when he collaborated with Floyd. He later became known as one of the nation’s leading African American artists and was often compared with Henry O. Tanner. In his early career, Adams established the art department at Morris Brown College in Atlanta and created illustrations and cartoons for The Voice of the Negro. He worked throughout his life with W. E. B. DuBois, illustrating for The Moon Illustrated Weekly, The Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line, and The Crisis. REFERENCES: Blockson 8762; Bieze, Michael. “Adams, John Henry, Jr.,” Oxford American Studies Center online; “Late Literary News,” Afro-American, 30 Sept. 1905, p. 4; Mitchell, Michele. Righteous Propagation: African Americans and the Politics of Racial Destiny (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), p. 129; Morgan, Lynda. “Reparations and History: The Emancipation Generation’s Ethical Legacy for the 21st Century,” The Journal of African American History, Vol. 99, No. 4 (2014): p. 404.

Item #7556

Sold