Notes of a Trip to California As a Member of the Columbus and California Industrial Association.

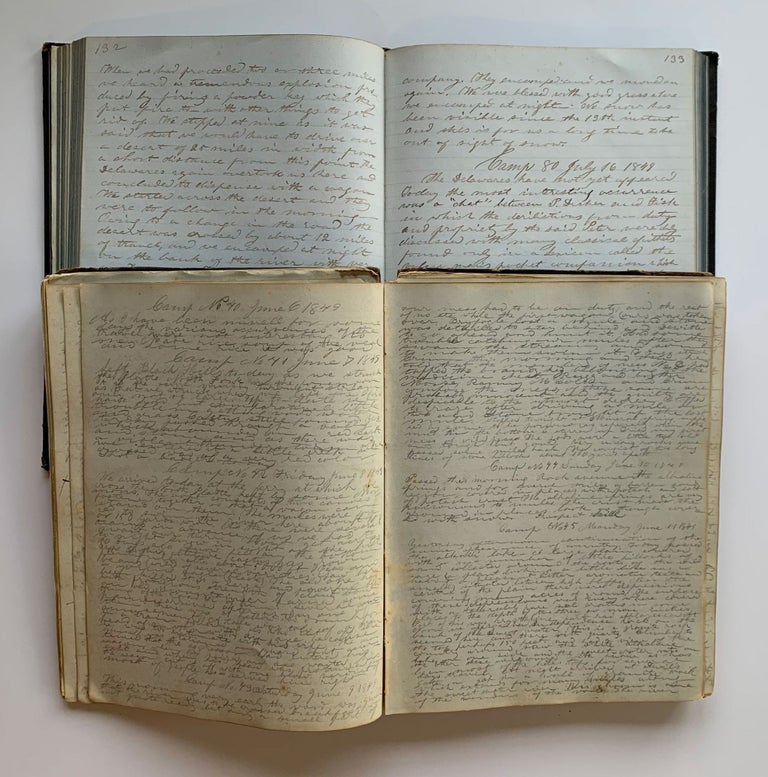

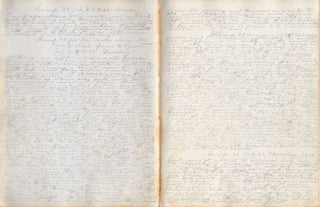

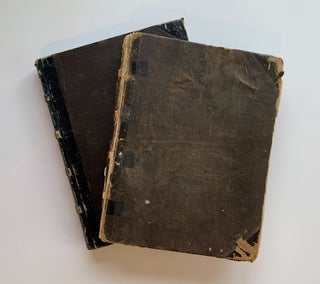

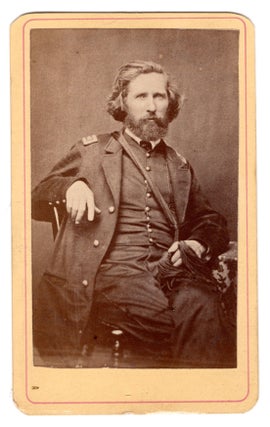

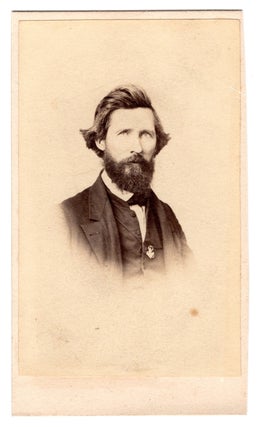

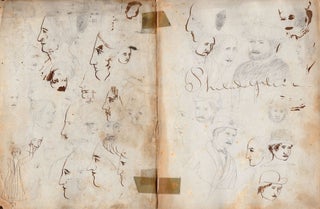

Various locations en route overland to and in California, 2 April 1849 to 16 September 1849. Small 4to (10.25” x 8”), half black leather (spine largely perished) and black cloth over boards. Manuscript title leaf, 55 densely written pp. of gold rush diary in ink and pencil, 19 pp. medical notes apparently dating from 1857 (some in English, others in Latin), 89 pp. of manuscript plays (evidently not Boyle’s hand), numerous pen & ink portraits on preliminary leaves. CONDITION: Covers detached, leaves broken into several sections, paper generally in good condition, small tape repairs to inner edges of a few leaves. [with] Boyle, Dr. Charles E. California[:] A Travel Over the Plains and Residence in the Land of Gold. Various locations en route overland to and in California, entries from 2 April 1849 to 26 August 1849. Small 4to (10.25” x 8”), half black leather, raised bands and gilt rules, black cloth over boards. 175 p. manuscript in ink, additional blank leaves. Pen & ink sketch of Sierra foothills on front endpapers. CONDITION: Very good, moderate wear, one detached leaf. [with] [Boyle family photo album with carte-de-visite portrait of Dr. Charles Boyle as a surgeon in the Civil War.] 4to, full embossed brown leather, metal clasp at fore-edge. 13 cabinet cards, 31 cartes-de-visite, 8 cdv-size tintypes, all mounted in windows in stiff leaves; 34 additional loose photos of various formats and dates laid in. [with] Various manuscripts by Charles Boyle, including: [Translation of Warlike Adventures of a Man of Peace by Zschokke.] 4to, gathering of leaves sewn together. 81 pp.; Practical Grammar. 4to, gathering of leaves sewn together. 9 pp., additional blank; Home Happy: Read Reflect and be Wise. 4to, gathering of leaves sewn together. Title leaf, 18 pp. (incomplete). [with] A wooden carving of a seated man by Dr. Boyle. [with] Columbus Dispatch Photo. A press photograph of Boyle’s grand-daughter Ada seated at a table with his diaries and carvings. September 27, 1949. Silver print, 9.5” x 7.5 plus margins. Photo credit and production notes on verso. [With] Miscellaneous documents, including Boyle’s medical school certificate, typed obituary, typed list of members of the Columbus and California Industrial Association, variety of family papers, photos, etc. The original 1849 overland diary of a brilliant doctor, naturalist and polyglot from Columbus, Ohio, tracing his passage to the California gold fields via the Oregon Trail as a member of the Columbus and California Industrial Association, with a revised version of the diary evidently written in California during the author’s stay there, along with other Boyle artifacts, including two carte-de-visite photographs of him, one showing him in uniform taken when he was serving as a surgeon during the Civil War. Dr. Charles Boyle (1821-1870) was born in Blacklick, Pennsylvania, and moved with his family to Columbus, Ohio, when he was a young boy after his father found work there. Educated locally and especially adept at languages, Boyle worked as a printer and then as public school teacher, but soon decided on a career in medicine, entering Starling Medical College (a forerunner to the Ohio State University College of Medicine) in the 1840s. Studying under Professor Samuel M. Smith, he obtained his degree in February of 1849 and began practicing medicine in Columbus. Boyle married Catherine Emma Deffenderfer (1823-67) in 1842, with whom he had seven children. Soon after entering the medical profession, Boyle was, like so many men at the time, struck with gold fever, and in April of 1849, left his wife and three young children for California as the official physician member of the Columbus and California Industrial Association. In California, Boyle prospected for several weeks on the South Fork of the American River in the region of Coloma, near Sutter’s Mill, but appears to have spent most of his time providing medical attention to miners and is known to have had a practice in Placerville in 1850, both offering medical services and selling medicine. In addition to mining and doctoring, Boyle collected vertebrates and invertebrates near the south and middle forks of the American River in El Dorado County, forming a small but important California natural history collection, which was subsequently one of the first such collections acquired by the Smithsonian (Boyle corresponded at some length with Spencer Fullerton Baird, the Museum’s Assistant Secretary). There are at least two California species named for Boyle: the brush mouse (Peromyscus boylii) and the foothill yellow-legged frog (Rana boylii). In the fall of 1850, Boyle moved to San Francisco, apparently continuing to practice medicine there until deciding to return home. He and several others built what has been described as a “sailboat” but must have been a small schooner or something of the sort, which they sailed around Cape Horn to Norfolk, Virginia, arriving in the spring of 1852. Upon returning to Columbus in April, he resumed his medical practice, with offices at 214 South 7th and 230 East Main Streets. During the Civil War, Boyle served as surgeon in the 9th Ohio Regiment, achieving the rank of Captain. In addition to his skill in medicine and knowledge of the natural world, Boyle was “an accomplished linguist (fluent in 32 languages)” and a public speaker, “much in demand for local meetings and clubs due to his vast knowledge, phenomenal memory, and often accurate predictions of future events” (Jennings). He was also known for his altruism, devoting much of his time and medical attention to the poor, and ultimately dying in poverty himself. Offered here are both Boyle’s original overland diary as well as a revised version, written in nearly identical volumes, perhaps suggesting that both accompanied him to California having been purchased together prior to his trip west. The summary which follows, as well as the subsequent representative passages, are taken from Boyle’s original diary (not the revised version), which includes entries for every day from the time of the company’s departure through Boyle’s final entry in California on Sept. 16th. The original includes two weeks worth of entries at the end that do not appear in the revised version. Excerpts from the revised, expanded and sometimes embellished diary were published in the Columbus Dispatch in October and November of 1949. The diary has not been published in its entirety nor in its original form. One of the members of Boyle’s Company was Peter Decker, whose diaries, owned by the Society of California Pioneers, were published in 1966, edited by Helen Giffen. Boyle mentions Decker many times and vice versa. Giffen’s introduction provides excellent background on the Columbus and California Industrial Association and helps to clarify some of Boyle's references. Unusually well-written and brimming with interesting details, as one would expect from a man with his gift for language (he read Shakespeare on the trail), Boyle’s diary is considerably more interesting than that of the average overland emigrant. Lending additional appeal to the original diary are numerous portrait sketches on the endpapers, most of which appear to depict members of Boyle’s company. In one of these a man wears a hat with an eagle insignia on it. Boyle mentions in his journal that the members of the Columbus and California Industrial Association wore an eagle emblem on their hats. Sketches of the foothills of the Sierras appear on the paste-down and flyleaf of the revised journal—another piece of evidence perhaps suggesting that Boyle’s revised text was written in California. The Diary On 1 April 1849, following an emotional farewell gathering with family and friends, Boyle and his company depart Columbus, making their way to the town of London. On April 3rd the party proceeds to Charleston, then to Cedarville, where they gear up and Boyle— invoking Izaak Walton—does a little unsuccessful fishing, along with a companion. From Cedarville they continue to Xenia, at times followed by women and children who run to see “the gaudy flag we carried and admire…the eagles with which our hats were decorated.” The company arrives in Cincinnati on the 5th of April, where they board the steamer John Hancock for passage to St. Joseph, Missouri, their jumping off point for the trail west. They begin their journey down the Ohio on the overcrowded vessel the following day. During a stop at Louisville, they have the opportunity to see “Mr Porter the Kentucky giant who is seven feet eight inches in height.” On the 8th they nearly lose a member of their party, one McColm, who falls into the Mississippi while attempting to get a pail of water, but fortunately is rescued. Following a two day stay in St. Louis, where there are rumors of cholera, the company proceeds upriver to the mouth of the Missouri, Boyle and the Walton brothers collecting fresh water from the clear side of the Mississippi before ascending the muddy Missouri. On the 12th, Boyle is called upon to treat Charley Breyfogle, who mistakenly believes he has cholera (a prevalent fear). More concerning, a fire breaks out aboard the Hancock, but fortunately it is extinguished with little incident or general alarm. The Steamer arrives at Independence Landing on the 15th and Boyle and Decker investigate the town itself, some three miles distant, encountering encampments numbering some 1500 to 2000 “Californians.” Upon returning to the boat they find “several well dressed men drinking at the bar,” one of them wearing “pantaloons trimmed with velvet and gold” who proves troublesome and is thrown off the vessel. They proceed upriver to the “the boundaries of civilization,” reaching St. Joseph on April 16th. Soon after arriving, Boyle has his hands full providing medical care to McColm, who still believes he has cholera, and John Walton, who was kicked in the head by a mule. On the 21st the main party crosses the Missouri to establish a new camp, while Boyle stays behind with McColm who is steadily recovering. On the 23rd they cross the river to re-join the party at Camp No. 2. The company remains in camp for a few days while making final preparations and while there Boyle observes (and subsequently shoots) “a small animal throwing up dirt” whose activities and characteristics he describes in considerable detail. In the afternoon of the 28th, the company finally gets under way, traveling some five miles to establish Camp No. 3. On the 30th they establish Camp No. 4, where they examine “an Indian grave in a tree top that is a trough dug out of a log.” Over the next two days they traverse the rolling prairie, passing a village of the Sacs and Foxes and an Ioway mission along the way, before camping on the Nemahow on May 3rd, where they encounter “a quarteroon Frenchman of the Pottowatamie nation with his wife (white) and a white Frenchman who had left his Pottowatamie family with her people.” Boyle converses on the subjects of Indian customs and history with the “quarteroon” who speaks Chippewa, “Sack,” and Pottowatamie as well as French and English. During a delay due to heavy rain, the company forms a “treaty of alliance” with a company from Illinois, adding another five to their train of ten wagons. They continue on their way on May 6th reaching “a beautiful stream, the largest we have had to encounter” in the afternoon, which they manage to ford largely without incident, although “Walton lost part of his coffee in carrying it across.” Pressing on, over the next few days the party sees antelope, experiences the nightly howling of the wolves, and passes buffalo skulls with messages by other emigrants written on them. Boyle takes supper sitting on a pair of enormous elk horns and once again tries his hand at fishing, to no avail. On May 12th, while at Camp No. 15, the company undertakes its first buffalo hunt, which ends in an encounter with some fifty Cheyenne braves, who prove to be friendly, providing particular relief to a few in the party who trembled in their boots. After following the trail as it meanders along the Little Blue River, the company reaches the Platte River on the 13th and Fort Kearney (then known as Fort Childs), “consisting of several sod built houses,” on the 14th. There they learn that the Cheyennes they had encountered were part of a larger war party on a campaign in Pawnee country. They see at the fort a Pawnee boy the troops had rescued from the Cheyennes, who had taken him captive after they scalped four members of his family. While at the fort, Boyle converses at length with a gifted African American interpreter from St. Louis. Continuing on the south side of the Platte the next day, the party catches a mess of fish in a small stream and Boyle finds the skull of a young person he takes to be a victim—presumably Pawnee— of the Cheyennes. On May 16th the party encounters a train of Mormons from Salt Lake City bound for the states and on the 18th they come upon a camp of traders with several wagons loaded with “buffalo skins and other pelts,” from whom they obtain some fresh buffalo meat, some of which Boyle eats raw, pronouncing it “good and sweet.” On the 23rd, the party reaches the upper ford of the south fork of the Platte where they are surrounded by many “Indian men, women and children who begged anything eatable they could and picked up the grains of corn scattered by the mules.” The company continues along the north fork of the Platte on the 26th, Boyle, Decker and Pike taking the opportunity to ramble about Castle Bluff, “composed of sand and fine pebbles cemented together with lime.” On the 27th Tommy Davis gets excited about a parcel of buffalo robes he sees in a tree and won’t be convinced that it is “the last resting place” of an Indian until the party comes upon a similar parcel in the hollow of a tree that contains the remains of a “papoose.” On the 29th Boyle and others walk two hours to Chimney Rock, where Boyle shoots a rattle snake with ten or twelve rattles. They climb the rock and record their names. While traveling through the hills some distance from the Platte on the 31st the company comes upon a blacksmith shop operated by one Robidoux, where Boyle is surprised to find the proprietor has a Webster’s dictionary as well as some other books. They reach the junction of the Platte and Laramie Rivers on the 2nd of June, the location of a fort of the American Fur Company. Here they cross the Platte and encounter on the other side “parts of several companies of Californians,”some of whom were abandoning “their wagons and every thing but the most absolute necessaries as they had overdriven their mules.” The company reaches the Black Hills on the 3rd of June and meets a lone Dutchman on the trail who had parted from a company out of Fort Smith, Arkansas. They grant him permission to travel with them. On the 4th, Mount Laramie has come clearly into view and on the 5th some of “the boys” shoot a buffalo calf but run out of ammunition before it is dead and have to finish it off with their bowie knives. Boyle finds the meat a bit too gamey. By the 7th the party is out of the Black Hills, striking the north fork of the Platte in the morning and later crossing a valley abounding in red earth and stone. They reach the Mormon Ferry at the north fork on the 8th, the boat consisting of “two canoes fastened together so that a wagon can stand on them.” While there the party hears a tale of a man in a train following theirs who beheaded another man with an axe for getting intimate with his wife. On the 11th the company comes to Independence Rock, which Boyle climbs to “perhaps 150 feet” and has a view of the country around, including a white alkaline lake on one side and the Sweetwater River on the other. At night they arrive at Devil’s Gate, “a gap in a wall of granite rock which extends for many miles” along the Sweetwater and “one of the wonders of the world,” the water rushing through “the narrow gorge with great rapidity roaring and raving as it meets the obstructions offered by the vast rocks lying in its narrow bed.” On the evening of the 12th the party learns of some Crow Indians possibly in the neighborhood and takes precautions. Boyle explains that the main issue with them is their mode of trade and relates two anecdotes of Mormons who were badly treated, one of whom was stripped and given “a bow to complete the swap.” On the 15th the party is pressing onwards toward South Pass. They meet “a Mexican going alone to the diggings” who “had quitted the telegraph Train on account of bad usage” as well as a group of Indian traders out of Fort Bridger, some 140 miles distant. The Wind River Mountains have come into view far to the right of the trail. On the 16th they make their way through South Pass, at noon coming to “Pacific Spring the first met with that sends its waters westward to the great Pacific Ocean,” a few miles west of the pass. They camp ten miles further on that evening, Fisk, Breyfogle and McColm suffering from altitude sickness, while Boyle and others experience “some difficulty of respiration.” The party arrives at a fork in the road on the 17th and following some deliberation and consultation of guide-books takes “the right or cut off road” (the Lander Cutoff). They arrive at the Green River on the 19th, are ferried over, and encounter a friendly band of Snake Indians, with whom they trade. On the 24th they come to Smith’s Fort (“Smith is a jolly fat one-legged man has many horses and plenty of cattle”) and on the 25th they reach Soda Springs, which Boyle pronounces “one of the greatest curiosities we have seen on the road.” On the 27th the company camps on a hill in sight of a deep gorge and trades with some Indians, Boyle complaining of “the nasty scamps eating the vermin they caught in each others heads and on their persons.” The party arrives at Fort Hale, a Hudson Bay Company trading post, on the 29th, and on the 1st of July they pass American Falls, where the “river Lewis is hemmed in between two ledges of volcanic rock and descends in a narrow converging bed about 30 feet and then on the north side falls perpendicularly about 30 to 40 feet.” On the 5th of July Boyle returns “to an old camp when the train had proceeded about 2 miles for a horse which had remained” and finds the horse surrounded by a small party of “Paunrack Indians,” one of whom lassoes the horse and hands the rope over to Boyle. The party is also overtaken by the Delaware (Ohio) Company, with whom they had traveled briefly early in the trip and now travel again. By the 8th the Humboldt Mountains are visible and the party reaches a headwater of Mary’s River the following day, enduring much dust and heat and finding four dead oxen on the road. On July 10th Boyle notes the loss of his Spanish Grammar “which Herd found traveling on the bottom of the Humboldt.” The company continues along the river bottom for a few days, then on the 14th crosses a twelve mile stretch of desert and camps “on the bank of the river with good grass.” The dusty, alkaline region continues to test the company’s fortitude and on the 19th Boyle and Raney are tasked with trying to catch up with a train that had carried off one of the company’s mules, soon finding themselves some fifteen or twenty miles in advance of the party. On the 21st they arrive at Sulphur Wells, where “many persons were encamped preparing to cross a desert of 45 or 50 miles to Carsons River,” and learn that the mule was returned to the company. Here Boyle contemplates the gloomy desert prospect before them, which he describes in some detail, and makes the acquaintance of fellow emigrants representing nearly every state “stopping to rest their tired animals before setting out to cross the desert.” Boyle sleeps that night on withered grass crusted with salt and the company spends the next day and the following making preparations to cross—cooking, cutting grass, storing water, etc. He notes of other trains arriving that they strangely recall “descriptions of Asiatic and African caravans.” They begin crossing the inhospitable waste at 3:00 pm on the 24th, encountering abandoned wagons and dead animals, and occasionally spotting wolves that feed on the carrion. On the 25th, in the midst of the howling desert wilderness, Boyle notes: “Decker and I were left yesterday to watch the wagon and bask in the sunshine and all afternoon I slept to make amends for the loss of sleep for the night before. At night read the Taming of the Shrew.” The following night he reads Hamlet and King Lear. The party concludes its grueling passage across the first of two deserts on the evening of the 25th and encamps on the bank of the Carson River where their cattle and mules are wounded by the arrows of Digger Indians, a few of whom also draw their bows on some of the men. On the 27th Price and Barcus start ahead of the company for the gold region, which is still 140 miles distant. After several more days of desert travel, the party finally reaches the foothills of the Sierras on the 31st, soon finding themselves in beautiful though challenging terrain. On the 2nd of August they enter a canyon, where Boyle is struck by “the immense height of the wall of rock that encloses the gorge estimated by our men at from three to five thousand feet.” They make their way through a tortuous rocky passage requiring ‘the united strength of men and mules to force our wagons up and restrain them when going down.” Here Walton’s wagon is broken and Boyle and others of “Mess 2,” finding that their mules can no longer pull their wagon, give it to Walton and undertake “a toilsome march over rocks and bogs and mountain streams with badly arranged packs which required frequent adjustment to keep them on the mules’ backs.” Sick from exhaustion at the end of the day, Boyle has no supper, drinks a cup of coffee, and lays down to sleep a while in a crack in a rock. The following day, the party encounters a cheerful company of emigrants returning from California, some of them Mormons, who inform them that the road is even more difficult ahead. On the 10th, the company rests at an encampment in anticipation of a forty-five mile march through country with no grass. Here they decide to head for Sutter’s Mill instead of Sacramento. Having camped in a valley filled with emigrants, the company leaves early the next morning arriving at the diggings at Weaver Creek, where they encounter Spaniards, Peruvians and Chileans with whom Boyle is able to speak Spanish, having studied his Spanish grammar on the trip. On the 11th they arrive “at a spring about 5 miles from the mill [Sutters]” and decide to “remain until the sickly season” is over, although their resolve apparently soon evaporated. Boyle visits Coloma on the 14th and 15th, where he intends to take up quarters. He notes that prices for medical attention are exorbitant, “$10 per visit in town $16 for bleeding or tooth pulling.” On the 17th the company gathers and votes to disband and divide their property, Boyle getting the medicine chest. The final month of entries finds Boyle both trying his hand at gold digging and practicing medicine. He also evokes the not infrequently violent scene around him, noting several murders. In one of his final entries he writes: “saw the skull of a murdered man. He was killed by a blow to the head with a crowbar on the right malar bone…must have died instantly.” Some Representative passages London, Ohio, 2 April 1849 “The hour of parting had been awaited with anxiety as thought of separation for a long period of time, the uncertainty of our ever returning and the dangers and difficulties to which we were about to expose ourselves rendered our feelings most sad and sorrowful. The moment arrived at last and its pains I wish not again to experience. Yesterday I gathered my little ones and wife around and tried to enjoy their society but the hour of separation was fixed and that ever saddened the moments which otherwise might have [been] joyous in the extreme. This morning Miss Decker presented us with a flag, the emblem of our country, to which was joined the insignia of our association, and in the address she delivered reminded us that the sight of that flag would serve to remind us of our happy homes and the virtuous influences they would extend around us in our journeyings in the western wilds…” Xenia, Ohio, 3 April 1849 “After taking a good hearty breakfast we all set to work gearing up our various mule teams. This to one expert in the business and not having any other animals than staid horses is a short and easy job, but for such a one our awkwardness and the antics of our mules would have been a perfect mine of amusement. As it was, there were some two or three hundred men and boys around us to offer advice and scare our mules by assistance attempted but not given…On we went from Cedarville to Xenia and as we went women and children ran to see the gaudy flag we carried and admire our strange [?] and the eagles with which our hats were decorated…” Cincinnati, 5 April 1849 At 10 A.M. today we arrived at the Queen City. Found our boat ready to receive our baggage and mules. The mules we put on board at once and with very little trouble. We took our wagons to pieces, had our bread boxes filled and packed on board and then went through the city to make a few purchases and were beset by Jews on all sides who were ready to sell anything at any price they could get and were at times quite troublesome with their anxiety to equip us to their liking. During our stay in the city the fire bells rang several times but the citizens paid no attention to the matter, leaving it all to the corps of firemen who appear to be very efficient… Steamboat John Hancock, 6 April 1849 Last night we were all on board and started on the beautiful Ohio. The boat full of passengers presented a scene of very great interest. Old men, young men and boys starting for the modern perhaps the ancient Ophir. I was fortunate in obtaining a state room with L. A Denig, in which I deposited my arms, medicine chest and lastly my wearied limbs. In the morning I was aroused by the stir made in the hall by the passengers getting up and turned out to see what was doing. When the state room door was opened I saw a scene which would require greater power of description than I possess to depict. In the hall some hundred and fifty feet long and twelve to fifteen wide there were as many mattresses spread as would fill the space and on these mattresses as many passengers lay as could well be pasted down in one [?] and the conclusion came to was that it was thicker than “three in a bed and one in the middle.” Well after a time we were all up and washed and ready for breakfast. Here a scene took place well worth noting. There were enough passengers on board to occupy three tables the size of the one on board and there was a regular tussle to see who should first sit down…During the afternoon we reached Louisville…Near the lower lock on the canal we went to see Mr Porter the Kentucky giant who is seven feet eight inches in height and tolerably well proportioned. He is the largest specimen of the genus homo I have ever seen. The sight of Mr Porter only confirmed in my opinion that a man of about the ordinary size is better calculated for pleasurable living as one so large as he or so small as Tom Thumb alias Major Stevens who was kissed by Queen Vic. Steamboat John Hancock, 7 April 1849 Charley Breyfogle was extremely well pleased with this his first trip on the Ohio this far down. Decker also sat with [?] on the forecastle. Chadwick, Fisk, and others had by permission of the captain a dance to themselves on the hurricane deck and they did “go it,” in the peculiar style they are apt to exhibit in anything they do. Steamboat John Hancock, 8 April 1849 This morning Sabbath we turned out early as the mess to which we belong consisting of Price[,] McCumman[,] Decker[,] Crist[,] Fisk and myself had the care of the mules for the day as had Mess No. 1 yesterday. Our mules were all fed and watered before breakfast, and we assembled on the hurricane deck to catch the first glance of the Father of the Waters on whose bosom in a few minutes we were about to float…During the process of feeding and watering our mules in the evening McColm in attempting to draw a bucket of water slipped from the guard into the river. Price was standing beside him and seized him by the foot but was unable to hold him. The terrible cry “man overboard” was the first intimation I received of the accident and did not learn who it was for some time afterwards. The yawl was manned and launched and the steamer Atlantic which [was] on the downward trip hove to and sent her yawl which was the first to reach Mac, who [was] sustaining himself well by swimming. He was picked after remaining in the water about five minutes nearly exhausted by [but] not at all daunted but very much chilled by his long sojourn in the embrace of the Father of the Waters. A cup of hot coffee and a snooze between a couple of blankets restored his energies so much that he got up for supper. The danger he was in may be estimated by the statement made by the captain who has followed the river for many years that he was the second man ever picked up after falling into the Mississippi from any boat he had been on. This afternoon we passed the Missouri bound upwards from N. Orleans, which had stopped to take in wood and bury a man who had died on board probably with the Cholera but what disease we could only conjecture. Many of our passengers were however considerably alarmed and there were sundry and diverse belly aches and undefinable feelings to be medicated for as we approached nearer and nearer to St. Louis as it is the conjecture that Cholera exists there in a rather aggravated form. Steamboat John Hancock, 11 April 1849 When we came up near the Missouri mouth as we [were] sailing on that side of the river which contains the clear water of the Mississippi J. and G. Walton and myself thought that we would have one last drink of clear water and afterwards take the sand bars of the Missouri, which within a short distance of the mouth gives character to the Mississippi for the rest of its course. Also saved a bottle for future use. Steamboat John Hancock, 12 April 1849 Last night about 12 P.M. Charly Dewitt came to call me to prescribe for Charley Breyfogle who to use his own expression has “decided cholera” but when duly examined it proved to be a very mild case of diarrhea resulting from indigestible food. He lay in his bed all day and notwithstanding his assertion to the contrary was very solicitous as to the result and it took all Walton’s argumentative prowess as well as my own to establish his mind in the belief that he was not dangerously ill. Today a thrill of horror shot through my frame to find the boat on fire. This to me when on land is rather a small matter but the situation in which we are placed renders the occurrence of fire a dreadful thing as but few of those on board would by any possibility reach the shore in safety…The fire was extinguished without alarming the passengers… Steamboat John Hancock [and Independence, Missouri], 15 April 1849 This morning about daylight we arrived at the landing near Independence which is about three miles back of the river. Along the landing there are a few log and prairie houses and back of these a high steep hill composed primarily of dark compact limestone containing a few shells and some very beautiful crystals of carbonate of lime. After breakfast I and Decker started for the town and found the road hilly and not very good. Vegetation not so far advanced as it was in Columbus when we started from home. Passed several encampments of California adventurers, mostly from the Buckeye state. Reached the town and was well pleased with the location and apparent thrift and neatness of the place. Here we saw several followers of the prairie, Santa Fe traders and one or two Mexican greasers, yellow and ugly. In the vicinity of the town according to the most accurate information there were about 1500 or 2000 Californians encamped…On our return we found in the boat several well dressed men drinking at the bar. One of them had his pantaloons trimmed with velvet and gold and was the great one among them. After a little while he interfered with the steward who politely requested him to make room for [?] but he and his friends were disposed to have a shindy. He seized a carving knife lying on the table but the passengers removed him, took the knife from him and put him on shore…Just at dusk we passed Kansas Landing and river and soon after Wyandotte city saw some few well dressed Indians on the shore and traveled thence forward…the limit of civilization was now reached. St. Joseph, 22 April 1849 Mac up and about and complaining of a sore mouth which I had expected but the mouth don’t quite meet these expectations. Walked over town and looked at the arrivals. Went up on the court house cupola [and] had a fine view of the country around and thought it looked about as picturesque as any I have seen for some time. The broad Missouri moving irresistibly but silently thro a narrow and beautiful valley enclosed by sloping irregular hills on each side. On the civilized side the prairie stretched down to the water’s edge and was dotted here and there with a grove or farm exhibiting the brighter green of cultivated vegetation. On the Indian side the bottom was thickly timbered but beyond this stretching away off to the south and west as far as the eye could reach the modulating prairie might be seen covered with the grass of last year’s growth grey and withered or with the early green grass of this year where that of last year has been burnt off. In one sport there was a fire on the prairie sending up clouds of smoke and by this the progress of the fire could be traced as it rushed onwards. On the hill side the strawberry, the wild plum and gooseberry were in bloom and besides these the lovely modest and familiar violet was to be found… St. Joseph, 23 April 1849 …went to Main Street and there saw a fight between an Indian from Puebla and a trader to the Iowas about some mules. Some white men borderers who took the Indian’s part exhibited the best horsemanship I have ever seen. The affair terminated without any serious damage except some awkward attempts on the part of the Indian to swear and he murdered Uncle Sam’s English horribly. Toward evening the boys brought a wagon over from camp for Mac and me and we started for the camp. In the course of the journey stopped several times and at last crossed the ferry and arrived in camp this west side of the Missouri and were fairly in Indian territory belonging to the Sacks and Foxes. Camp No. 2, 22 April 1849 This afternoon I observed a small animal at work throwing up dirt in the middle of our camp with no apparent fear. His motions were singular and rapid. Retreating into his hole backwards he would remain a few seconds and then return to the surface of the earth throwing our a quantity of dirt, look around and repeat the same maneuvre. I wished to examine him and after observing his motions for some time I shot him regretting at the same time the misplaced confidence he had displayed. He was a light brown color and about eight inch in length. Had a short tail like a mule. The fore feet were very strong proportionately[.] Teeth like rodentia, but the cutters were so arranged that they might be used without open[ing] the mouth being peculiar in this particular. But the most singular peculiarity was an arrangement by means of two large pouches one on each side of the neck for carrying out the earth he dug up. These pouches were large enough to contain more than an ounce of dirt each and were controlled by means of small but strong muscles… Camp No. 4, 30 April 1849 After supper looked at an Indian grave in a tree top that is a trough dug out of a log, with a lid, in this reposed the last remains of a fellow being some 20 feet above the surface. In the box was deposited his knife to fit him for the western paradise. Camp No. 7, 3 May 1849 Traveled about 15 miles today and encamped on the banks of a little stream said by some to be the “Big Blue.” The clear bright water was pleasant to look upon after having had no water except for the occasional puddle for some days. There were several parties encamped here and among them a quarteroon Frenchman of the Pottowatamie nation with his wife (white) and a white Frenchman who had left his Pottowatamie family with her people. Camp No. 8, 5 May 1849 Having made a treaty of alliance defensive and offensive with a company from Illinois we proceeded onward with a good and willing heart and camped at a little stream where wood and water were plenty and we encamped in a very pleasant plain. During the night we kept regular watch as hitherto but instead of standing three hours every other night it is determined that each man able to do duty shall stand watch one hour every night. The train now amounts to 15 wagons and makes a rather formidable appearance. And we suppose that we will be able to protect ourselves from the Indians. Camp No. 12, 9 May 1849 While stopping at noon we had a view of a pair of antelopes skimming over the prairie. They are beautiful animals, less in size than a deer, run with a kind of trot very swiftly. Have tonight a beautiful place to encamp. Took supper seated on a pair of elk horns of a large size. Saw several old buffalo skulls today. But at present too early to meet with the living animal. Camp No. 13, 10 May 1849 As we were moving along today we saw notices of our predecessors written on elk and deer horns and buffalo skulls. These evidences of the welfare and progress of others, of some known to us, gave great satisfaction. After supper patronized the favorite pursuit of Izack Walton unsuccessfully. The Little Blue along the meandering course of which we have been traveling for two days past is a very pretty stream very swift and clear but not a good stream for fish at least not in this part of its course. Camp No. 15, 12 May 1849 Today has been one of interest to us all and will long be remembered as the first buffalo hunt. We started early in hopes of reaching the Platte by night, it being some 30 miles distant and were making very good progress when suddenly about 9 A.M. the word passed along the line that a herd of buffalo was in sight…Walton, Fisk and others started off on horseback to get the windward of them…After a few minutes Barcus and others of us seeing partly colored animals supposed they were the oxen of some train of emigrants…After a little longer we could distinguish that the buffaloes were Indians on horseback and the advanced wagons returned to the main train which by this [time] had received information from G. Walton that they were Indians. The wagons were formed into a circle with mules in the centre and we formed a line between the Indians and the wagons…The Indians to the number of 35 or 40 rode down in good order to within 150 yards when Walton left the ranks and rode toward them. Their chief met him halfway, they shook hands, then the whole party came riding to within a rod of our lines, dismounted, seated themselves on the ground and we talked by signs a little while. They told us they were Cheyenne, denied being Pawnees and traded a little with the boys and then left for the north… Camp No. 17, 14 May 1849 …after about 9 hours travel we arrived at Ft. Childs (now Fort Kearney). This consists of several sod built houses covered with sod and are warm but rather dirty…Two or three families live here and the garrison consists of two companies of dragoons. Here we learned that the Cheyennes we had seen were out on an excursion into Pawnee country[,] that they had taken several scalps and one prisoner, a boy who had been released by the troops. I saw the little fellow at the fort with the interpreter attached to the station. He said that when the family was attacked they sent him to hide and after a time the Cheyennes drew him out of the hole when he saw that they had four scalps which he supposed were those of his father, mother, brother and sister. They tied him on a horse and carried him past the fort and as soon as captain Walker learned of this he followed them and released the boy. I here became acquainted with the interpreter, a negro born in St. Louis and raised among the Otoes. He was an intelligent fellow, spoke French, English, and several Indian tongues, had been in Paris and London and got a pension from the government for some rascality in an Indian treaty and 4300 yearly as an interpreter. Told me many things about the superstitions and customs of the Indians. Camp No. 27, 23 May 1849 About 11 today reached the upper ford of the south fork of the Platte…here we were surrounded by Indian men women and children who begged anything eatable they could and picked up the grains of corn scattered by the mules. They traded moccasins with some of the boys for a single cake or half pint of beans…The name the Indians (the Sioux) assume is Sahcotah which means cutthroat and when I asked one old fellow what he was he placed his hand on his breast and with great self-complacency repeated “Sahcotah sacotah.” They were dirty greasy miserable and were great beggars and even picked the pockets of some of the men… Camp No. 34, 31 May 1849 Travelled still farther from the river so as to pass round a hill called Scott’s Bluff…After 4 miles came to a blacksmith shop among the hills kept by Robidoux who has a Sioux wife. He keeps tinware and here 500 miles from any place a man may find Webster’s dictionary and other works to match, besides French works. Here we met 2 Mormons from Salt Lake. One had been to digg gold, was going to the states and was robbed by the Crow Indians… Camp No. 42, 8 June 1849 We arrived today at the ferry at which we cross the North Platte kept by some Mormons. The boat consists of two canoes fastened together so that a wagon can stand on them.The mules were forced to swim the river here about 100 or 150 yards wide. As there were several teams in advance of us we had to await our turn. Won’t get across to-night. Snow in sight on the hills. Ten days ago snow fell on the bottom up to this altitude…Saw here a young eagle (black). The old one had been killed. It is a large and powerful bird with prodigious strength of claw. Saw an old mountaineer and learned something of the road &c of him. Several companies arrived after us. In one of them there was a fellow too drunk for amusement. A tale was told of a man in a train following us who cut off the head of another with an axe because he was too intimate with his wife. The man had been stationed on guard but ascertained that the aggressor had entered his wagon, when he seized an axe, waited for him to exit and when his head was protruded from the wagon cut it off with one blow. Verdict of most of people—served him right. Camp No. 51, 17 June 1849 Today arrived at a spot where the road forks [and] considered for some time which to take[,] some of the teams preceding us having taken one some the other[.] Decided to take the right or cut off road which it was said would save 5 days travel. Capt. John consulted Ware and the Mormon guide as to the streams and we made for Green River. Passed two streams and on the bank of the last encamped and here found the road fork again and thought the books wrong… Camp 52, 18 June 1849 Took the right hand road again and traveled two miles or so and found the two roads reunited and found ourselves on the desert without water for the mules… Camp 62, 28 June 1846 Today we were accompanied nearly all day by Captain Pontius who was quite a talkative Indian. Could speak a little English. Had been to St. Louis. Said he had eaten one Sioux Indian. Stopped at night within a few miles of Fort Hale near a delightful spring. Indians staid with us. Camp 69, 5 July 1849 Returned to an old camp when the train had proceeded about 2 miles for a horse that had remained. Found half a dozen Paunrack Indians around him. Rode up to them. The oldest in the squad took a lasso out of my hand and threw it over his [the horse’s] head and then handed it to me. Rewarded him with a few rounds of ammunition and he to show his gratitude assisted me to the train with him. Canfield and Krumm returned armed to the teeth as I had no arms fearing that the Indians might take advantage of me and found me chatting with them as we were proceeding on towards the train. Camp 75, 11 July 1849 This forenoon travelled along the [Mary’s] river with several trains in sight before and behind. We hear nearly every day of Capt. Russell Lewis and others who went by Fort Bridger and so lost several days which we saved by going round by Fort Hale on the [Sublette] cut off. Yesterday we saw a Shoshone at noon very friendly and constantly repeating the name of his nation as a password to our respect. This morning another came in. Had a horn and wood bow, flint-headed arrows and like many others and especially our friend of yesterday ate the vermin on his head and person… Camp 86, 21 July 1849 This is considered to be the lower end of the sink of the Humboldt but a channel can be traced onwards and appears to drain the superfluous water of the valley at some seasons into some reservoir sink or lake farther south. The sulphur wells are dug in this channel [and] still contain water in places. Where this is the case rank bulrushes grow in the alkaline pools. Where the channel is dry a kind of cane thickly covers the ground. In all other parts of the valley as far as the eye reaches bounded on two sides by the horizon…nothing meets the eye but a desolate plain with here and there a spot which affords a meager subsistence to a few stunted bunches of artemisia. The mountains are bare rocks discolored by the heat of volcanic fires and all taken together the most gloomy and uninviting scene is presented… Camp 87, 25 July 1849 Decker and I were left yesterday to watch the wagon and bask in the sunshine and all afternoon I slept to make amends for the loss of sleep of the night before. At night read the Taming of the Shrew. Went to sleep and slept until sunrise it being thought unnecessary to watch as so many were all the time passing. Saw some Shoshones 10-12 and one Digger last night the former going to Fort Hall. The latter did not speak but altho in company with the Snakes held himself aloof. His only clothing was a breech clout…In the afternoon the trains were few that passed as the travel is mostly at night and in the forenoon…Read King Lear and Hamlet… Camp 92, 1 August 1849 This morning we found our road still continued up the valley of the Carson. After going some distance the valley here 5 or 6 miles wide appeared to be nearly all a mere swamp with numerous ponds grown full of reeds interspersed through it. Here we came to a spot where for some 100 yards numerous hot springs impregnated with sulphur arose near the margins of the swamp and affording a stream of water so hot that the hand could not bear it. The mountain here on the right or west side is from one to 4000 feet,—covered with a thick growth of pine then the valley with various colors and hues as the different species of plants are more dispersed and on the left another range which appears to be as high as the one on the right, but blue and indistinctly defined in the distance. Numerous cool and pleasant rills running from the hills united in the center and form a beautiful brook. Altogether makes up a very romantic and pleasant scene. Camp 99, 11 August 1849 Early this morning we were under way. Last night most of us slept with our mules 3 miles from camp to bring them up early. The place where we herded our mules was a beautiful little valley of about 2m surrounded by hills covered with lofty pines while the valley was a perfect prairie. There was a large number of animals on this prairie and the various owners encamped on the foot of the hills on all sides and thus prevented any animal from leaving the prairie. The various fires some 100 scattered along the hill sides all in sight, the frequent guns, the yells of mule and cattle herders all combined made it a strange and romantic scene. Well in the morning we moved off two carts 4 wagons, the remains of 10 with which we started. At noon took lunch…looked for gold a little but it was too deep. Drove on to Weaver Creek diggings. Spaniards Peruvians Chilians and some Americans are here. Met W. C. Stiles. He had made a little. Found that [I] could speak Spanish with considerable facility. Did not stop long but proceeded onwards 4 or 5 miles to the next dry diggings. Here we landed before dark, encamping under a beautiful tree in the center of the little valley which we learned was the gallows tree as three men had been hung on it…for robbery and murder after a fair trial by a jury of miners. Slept comfortably under the tree… Caloma, 20 August 1849 This morning went with Drummond McIlvain and Denison to examine a bar on the South or American fork. At 2 pm went into the village. Took boarding with Herd and went 2 miles to Williams Rancho for some baggage left there and returned by 10 pm. Went to bed and suffered in the flesh some on account of the numerous fleas which infest the place. Culoma is situated on the American fork of the Sacramento at the mill built by Sutter. The houses are mostly cloth covered frames. Camp 100, 7 September 1849 Worked all day and got about a dollar. This afternoon I heard about a man’s bones recently killed being found on the hills. A man was also found in the river murdered this week. Camp 100, 9 September 1849 Today tried my hand at gold digging. As yet it has proved very unprofitable, $100 being the greatest amount I have obtained at one days labor. Yesterday I observed as I passed through the woods the bark of several pines pierced with a vast number of holes and these upon close examination proved to be the receptacles of food—acorns—made by the woodpeckers of this region. These acorns are held fast by the pitch which exudes into the hole made by the woodpecker. A thoroughly compelling group of artifacts of a fascinating forty-niner. REFERENCES: Jennings, Mark R. “A Biography of Dr. Charles Elisha Boyle, With Notes on His 19th Century Natural History Collection From California.” The Wasman Journal of Biology, 45(1-2), 1987, pp. 59-68; Giffen, H. S., ed. The Diaries of Peter Decker. Overland to California in 1849 and Life in the Mines 1850-1851. Georgetown, California: The Talisman Press, 1966. “Introduction,” pp. 11-39; Mattes, Platte River Road Narratives 370; Bagley, Across the Plains, Mountains and Deserts, p. 38.

Item #8067

Sold