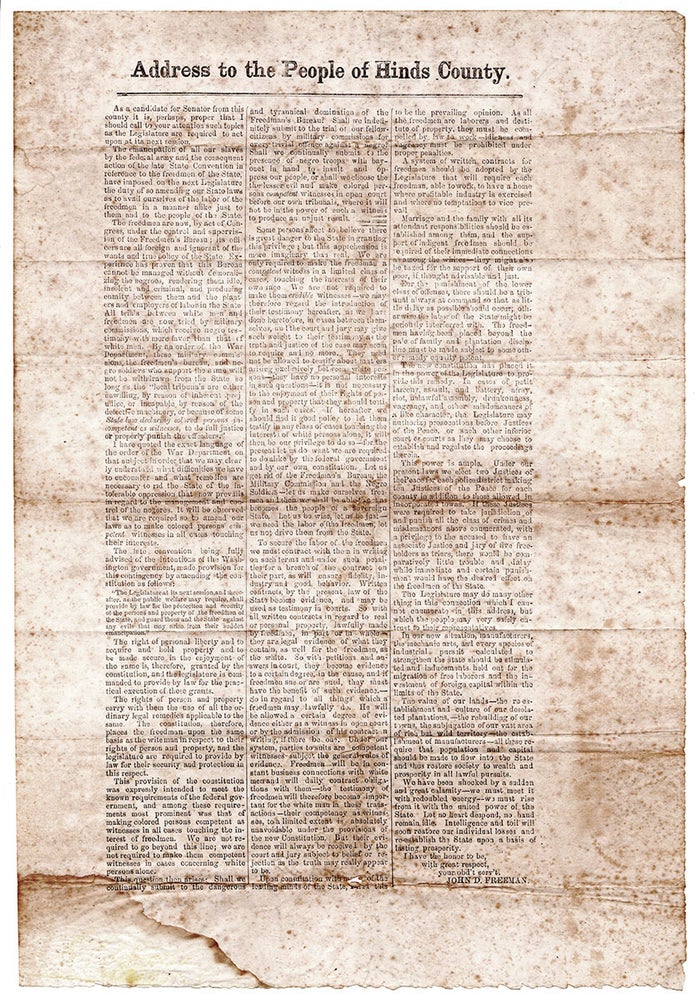

Address to the People of Hinds County.

[Hinds County, Mississippi, 1865.]. Broadside, 16” x 10.75”. A substantive, unrecorded, and exceptionally interesting broadside issued shortly after the end of the Civil War, addressing the shifting legal status and civil rights of freed African Americans in Mississippi and foreshadowing the sharecropping system that soon emerged. A candidate for State Senate representing Hinds County, Mississippi, John D. Freeman (1817–1886) here addresses voters and discusses duties to be undertaken in Mississippi’s next legislative session in response to an amendment to the state constitution passed at the Constitutional Convention of August 1865 formally recognizing the end of slavery in the state. Addressing the “sudden and great calamity” that has “shocked” Mississippi, “the emancipation of all our slaves by the federal army,” Freeman begins by noting that the next Legislature must amend Mississippi law to “avail ourselves of the labor of the freedmen.” Former slaves were then under the control and supervision of the Freedmen’s Bureau (est. 1865), whose officers, Freeman asserts, are “all foreign and ignorant of the wants and true policy of the State.” He observes that experience has proven the Bureau “cannot be managed without demoralizing the negroes, rendering them idle, insolent and criminal, and producing enmity between them and the planters and employers of labor in the State.” Further, he notes that all trials between whites and freedmen are now tried by Military Commissions—“which receive negro testimony with more favor than that of white men.” Directly quoting from a recent Order from the War Department, he notes the Bureau, the Commissions, and the African Americans who support it will not be withdrawn from the state so long as the “local tribunals are either unwilling, by reason of inherent prejudice, or incapable by reason of the defective machinery, or because of some State law declaring colored persons incompetent as witnesses, to do full justice or properly punish the offenders.” He quotes the Order’s language so “that we may clearly understand what difficulties we have to encounter and what remedies are necessary to rid the State of the intolerable oppression that now prevails in regard to the management and control of the negroes.” Freeman cites the 1865 Constitutional amendment that led to the present state of affairs in Mississippi to “provide…protection and security of the persons and property of the freedman of the State, and guard them…against any evils that may arise from their sudden emancipation.” He explains that the former slaves now have rights of personal liberty and to acquire and hold property granted by the Constitution, which the state legislature is now compelled to support. One important implication of the new legal status of African Americans is that they must become “competent as witnesses in all cases touching the interest of freedmen.” Freeman argues those who perceive “great danger” in granting this privilege are mistaken; he clarifies that “we are only required to make the freedman a competent witness in a limited class of cases…touching the interests of their own race.” What’s more, Freedman notes, “we are not required to make them credible witnesses”—and they need not be allowed to testify about matters arising exclusively between whites. On the whole, Freeman insists on not ‘going beyond the line’ demanded by the recently-amended Constitution. While Freeman recommends getting rid of the Bureau, the Commissions, and the negro soldiers in order for Mississippi to become a sovereign state, he nevertheless asserts they need the labor of freedman. “[L]et us not drive them from the State.” To retain this labor, he advises creating “written contracts” to ensure the fidelity, industry and good behavior of freedmen—contracts which can also be used as testimony in courts. Describing what soon became the sharecropping system in the South, he proposes a “system of written contracts” to require all African Americans to work and own a home, and spells out their responsibilities relating to family and marriage; taxation to support fellow impoverished African Americans; and their discipline and punishment (former slaves now “having been placed beyond the pale of family and plantation discipline”). Also proposed is a system of legal punishment for crimes and misdemeanors. Freeman concludes by outlining how to stimulate and boost Mississippi’s economy and to restore the value of their lands (including “our desolated plantations”). John Freeman moved to Mississippi in 1835 and was elected District Attorney in 1837. Serving as Attorney General of Mississippi from 1841 to 1851, he was elected as a Union Democrat to the Thirty-second Congress (1851–53). During Reconstruction he served as a member and Chairman of the Democratic State Central Committee. We have been unable to determine if he won his bid for State Senate. Moving to Canon City, Colorado in 1882, he resumed the practice of law and died there in 1886. No copies recorded in OCLC. A rare broadside reflecting efforts in Mississippi to preserve the essence of the slave-based economy and pre-Civil War social order. REFERENCES: “Mississippi; Important Action of the State Convention The Extinction of Slavery Recognized Freedmen to be Protected.” New York Times (23 Aug. 1865); Freeman, John D. at bioguide.congress.gov; Gen. John D. Freeman at findagrave.com CONDITION: Foxed, dampstained at lower left corner, browned along old horizontal folds, two tiny punctures to the text, partial loss to one word.

Item #5749

Sold