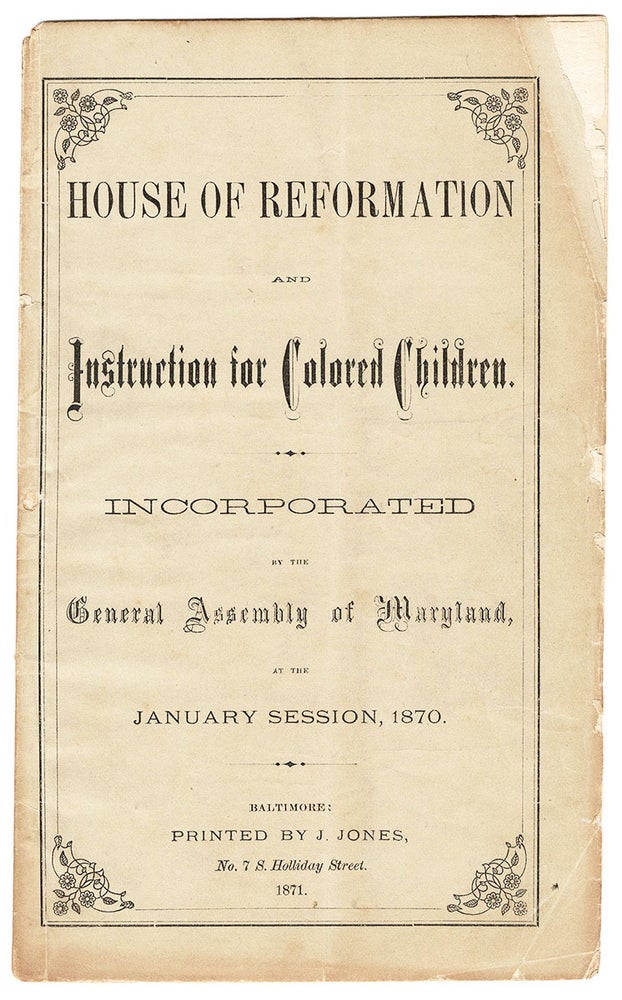

House of Reformation and Instruction for Colored Children. Incorporated by the General Assembly of Maryland, at the January Session, 1870.

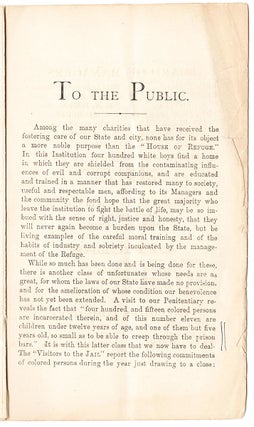

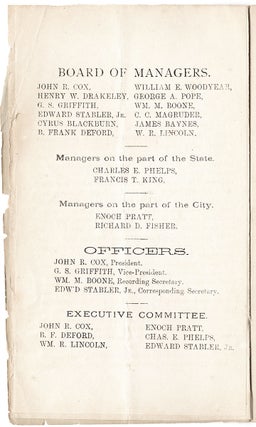

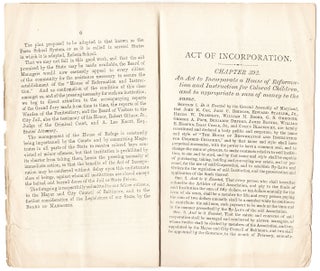

Baltimore: Printed by J. Jones, No. 7 S. Holliday St., 1871. 12mo (7.5” x 4.5”), printed wrappers. 16 pp. An appeal to the public for funds to establish a reform school for African-American boys in Maryland in the wake of emancipation, conceived as an alternative to the deplorable and corrupting circumstances of prison, with a view to creating a better educated and more productive labor force. As observed in the opening address to the public, at the time of publication Maryland had a reform school for white boys, known as the “House of Refuge,” but no similar institution for African-American boys. The Legislature had recently passed an act of incorporation for such a school, but funds were lacking. It is noted that a visit to the Penitentiary reveals that “four hundred and fifteen colored persons are incarcerated therein, and of this number eleven are children under twelve years of age, and one of them but five years old, so small as to be able to creep through the prison bars.” A recent “Visitors to the Jail” report noted that in 1870 some 2,335 black youths had passed through the prison doors, having been apprehended “for violation of the Peace and for Drunkenness,” “Larceny,” “Vagrancy,” etc. These crimes included such trivial offenses as stealing three loaves of bread, stealing 23 cts., etc., and many of the prisoners were children between the ages of five and sixteen. Maryland being dependent upon the large black population for labor, much of which had formerly been enslaved, the argument is made here “that a better use should be made of them than supporting them in our prisons.” In addition to the four-page “Address to the Public,” the pamphlet includes a list of the school’s officers and the Act of Incorporation. In 1870, Enoch Pratt (1808–1896), one of the leading businessmen in 19th-century Maryland, donated Cheltenham, a 752-acre tract of land and former plantation in southern Prince George’s County, to be used for the school. Pratt served as president of the school’s board for a number of years, and was also instrumental to the establishment of Baltimore’s public library system, believing “a free circulating public library open to all citizens regardless of property or color” to be the city’s greatest need. OCLC records just two copies, at Brown University and the State Library of Massachusetts. A rare pamphlet addressing the perennial problem of the incarceration of black youth in America. REFERENCES: Barbic, Kari. Enoch Pratt at philanthropyroundtable.org; Papenfuse, Edward C. Whatever Happened to Birdie Shine? Caring for the Children At The Johns Hopkins Colored Orphan Asylum, and its predecessors, 1867-1923 at rememberingbaltimore.net; Cheltenham (82A-042) at mncppcapps.org CONDITION: Chipping to edges of front wrapper, title-page, and the first few pages, but no loss of printing; contents generally clean.

Item #6218

Sold