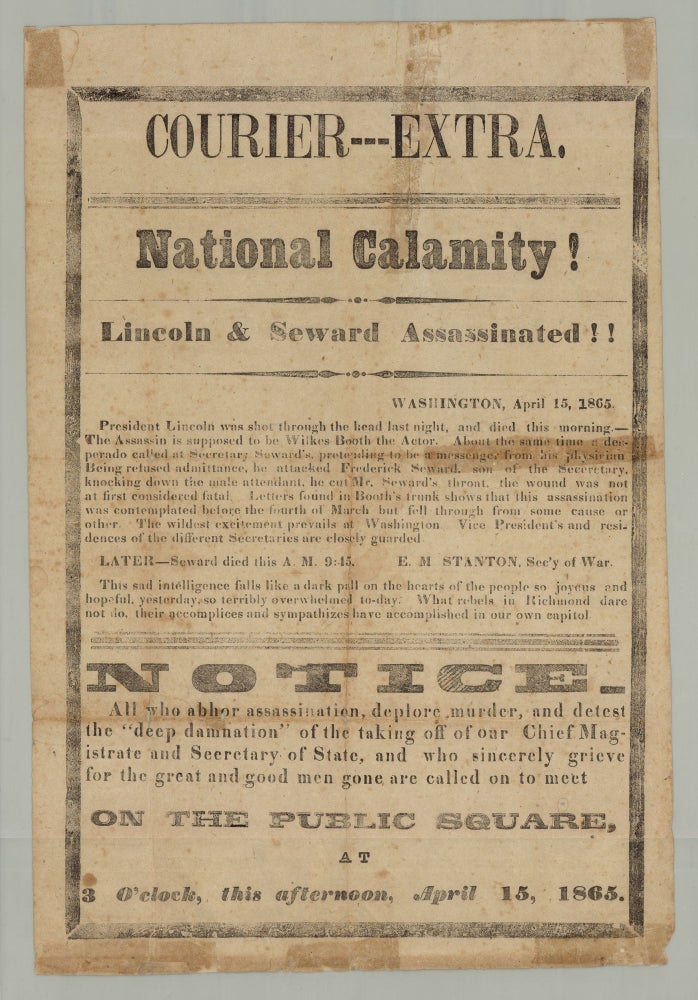

Courier—Extra. National Calamity! Lincoln & Seward Assassinated!! Washington, April 15, 1865. President Lincoln was shot through the head last night and died this morning…

[N.p., 15 April 1865]. Broadside on wove paper, 14.5” x 9.75” plus margins, text divided by rules into three horizontal sections, additional ornamental dividers, black mourning borders. CONDITION: stains from old tape repairs on verso showing through, the corresponding tears and separations now repaired with acid free document repair tape on verso; these include a 4.25 inch tear into text at top, a 4 inch tear along left of central horizontal fold, 5 inch separation along left side of vertical fold in lower third, a few small breaks at edges; a few small holes along old folds with minuscule losses to lettering. An exceptionally rare Abraham Lincoln assassination broadside issued the morning after the President was shot and during the brief period when it was thought that Secretary of State Seward had been assassinated as well, reflecting the extraordinary alarm and confusion surrounding these stunning events. Just one other copy of this broadside is recorded, which is held by the Library of Congress. After boldly announcing “National Calamity! Lincoln & Seward Assassinated!!,” the broadside reports the details as understood in the immediate aftermath of the President’s death: President Lincoln was shot through the head last night, and died this morning–The Assassin is supposed to be Wilkes Booth the Actor. About the same time a desperado called at Secretary Seward’s, pretending to be a messenger from his physician[.] Being refused admittance, he attacked Frederick Seward, son of the Secretary, knocking down the male attendant, he cut Mr. Seward’s throat, the wound was not at first considered fatal. Letters found in Booth’s trunk shows [sic] that this assassination was contemplated before the fourth of March but fell through from some cause or other. The wildest excitement prevails at Washington. Vice President’s and residences of the different Secretaries are closely guarded. LATER–Seward died this A. M. 9:45 E. M. Stanton, Sec’y of War. This sad intelligence falls like a dark pall on the hearts of the people so joyous and hopeful, yesterday, so terribly overwhelmed to-day. What the rebels in Richmond dare not do, their accomplices and sympathizes [sic] have accomplished in our own capitol. While both shocking and vivid, the details here, as in many early reports, are also relatively sketchy. In the case of Lincoln’s assassination there is no mention of Ford’s Theatre or the immediate circumstances surrounding or following the shooting. Seward’s would-be assassin, Lewis Powell, is identified only as “a desperado” (it was two days before he was identified as the perpetrator). Also unknown to this account are the names of others present (some of whom were attacked), including William Bell, Fanny Seward, Augustus Henry Seward, Sergeant George F. Robinson and Emerick Hansell as well as the name of Powell’s accomplice, David Herrold, who had been waiting with their horses and fled the scene prior to Powell’s emergence from Seward’s house. This staggering report is followed by a remarkable “Notice” reading “All who abhor assassination, deplore murder, and detest the ‘deep damnation’ of the taking off of our Chief Magistrate and Secretary of State, and who sincerely grieve for the great and good men gone are called on to meet on the public square at 3 O’clock, this afternoon, April 15, 1865.” The use of language from Shakespeare’s Macbeth (“the ‘deep damnation’ of the taking off”) is both ironic and excruciatingly appropriate, Lincoln and Booth both being great admirers of Shakespeare, and the tragedy of the event being inescapably Shakespearean. Booth played the lead in Macbeth in 1863 and the final entry in his diary, written when he was on the run following the assassination, is a quotation from Macbeth: “but ‘I must fight the course.’ Tis all that’s left me.” Just a few days before his death, Lincoln read to a group of friends a passage from Macbeth touching on the guilt-afflicted mind of the murderer. In an 1863 letter to actor James Hackett, Lincoln observed: “Some of Shakespeare’s plays I have never read, while others I have gone over perhaps as frequently as any unprofessional reader. Among the latter are Lear, Richard Third, Henry Eighth, Hamlet, and especially Macbeth. I think nothing equals Macbeth — It is wonderful.” The eerie parallel with Macbeth was not lost on the American public and various quotations from the play were invoked in other published sources of the time. The broadside was published by a Union city newspaper identified here simply as the “Courier,” which provides little basis for identifying the place of publication, as hundreds of Couriers were published at the time. The cataloging for the Library of Congress copy provides no further clues. While the locale in which it was issued is unknown, this broadside has tremendous appeal as a rare separately published account of the assassination and, unlike some broadside announcements of the time which consist mainly of quotations from official sources, embodies the emotional response on a local level to the tragic news. A rare and deeply stirring piece of Lincolniana. REFERENCES: Not in Stern, although described on the Library of Congress website as part of the Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana; Not in Monaghan; Ullman, Douglas Jr. Troupe Movements: The History of the Theatre During Wartime at battlefields.org; Haase, Kate. Lincoln & Macbeth: a Surprising Tale Told Through Primary Sources at teachingshakespeareblog.folger.edu

Item #7521

Sold