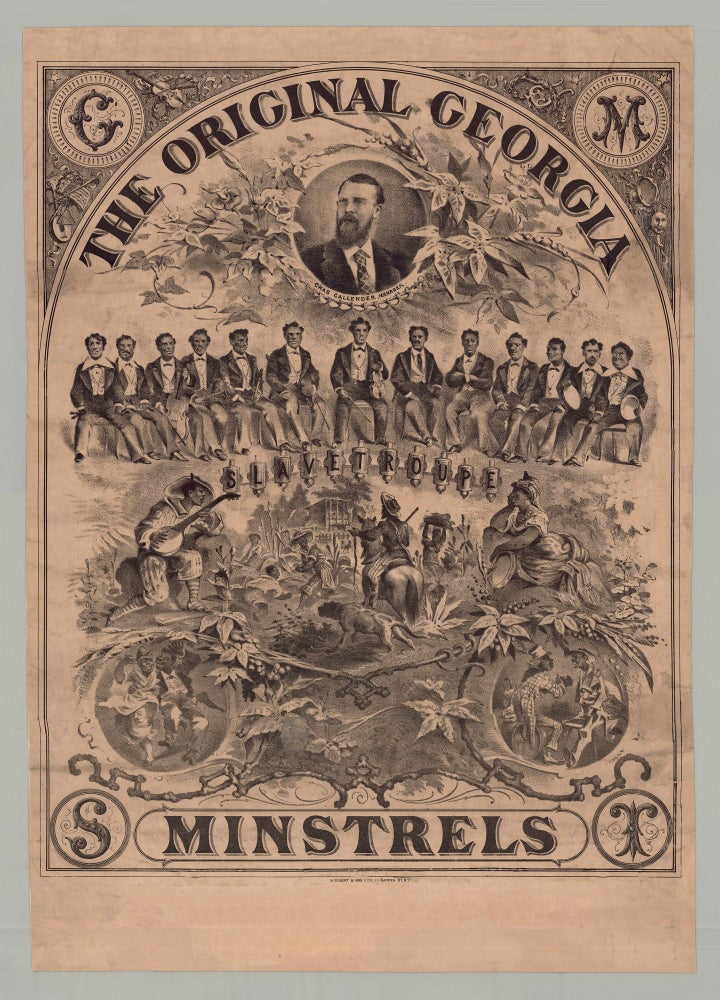

The Original Georgia Minstrels.

New York: H. Seibert & Bro., litho. 14 Warren St., [ca. 1872?]. Lithograph, 22.5” x 17”, plus margins. Printed signature of artist “A. Schwabe” in image at lower-left. A fascinating unrecorded broadside for one of the first successful, ‘genuine’ black minstrel troupes, which toured the U.S. and abroad, and appealed to both white and black audiences by emphasizing a connection to legitimate black culture as it developed under slavery. Among the first of the black minstrel troupes to gain popularity in the U.S. was a group of fifteen ex-slaves, originally of Macon, Georgia, called the Georgia Slave Troupe Minstrels. Organized in 1865 by W. H. Lee, a white man, the troupe toured during the 1865–66 season, becoming the first black minstrel troupe to enjoy a successful tour. Lee’s troupe soon came under the management/ownership of Sam Hague, a white minstrel performer. While Hague's group was drawing public acclaim, other groups calling themselves Georgia Minstrels toured the U.S.—one of them under the management of African-American Charles B. Hicks (ca. 1840–1902), who was also a minstrel performer. Hick’s Georgia Minstrels (also established in 1865) was composed of about a dozen musicians, some of whom were former-slaves. Of light brown skin, Hicks became one of the most successful black managers of minstrel groups—and the first black man to simultaneously own and manage such a company of his own. Despite the racist climate in America, Hicks operated the company for seven years, his company was soon regarded as on par with successful all-white companies. Hicks played-up his troupe’s connection to legitimate black culture, billing their act as an ‘authentic’ portrayal of black plantation life, and evidence suggests his company drew significant numbers of black viewers. (In 1869, a Pittsburgh newspaper reported that the "colored element of the city turned out en masse" to see Hicks’s Georgia Slave Troupe.) One ad for a minstrel troupe Hicks managed claimed the company was "composed of men who during the war were slaves in Macon, Georgia, who, having spent their former lives in bondage will introduce to their patrons plantation life in all its phases.” In 1870, Hicks and some of his members joined with Hague’s Great American Slave Troupe for a tour of the British Isles. In 1872, after returning to the U.S., Hicks sold his company to Charles Callender (a member of Hague's Georgia Minstrels), but stayed on as manager until 1873. Callender began recruiting new talented black personnel, and by 1873 his company comprised twenty men—including vocalists, musicians and comedians. In 1878, J. H. Haverly purchased Callender's Georgia Minstrels, and further enlarged the troupe size; Callender was retained as manager. From 1877 to 1880, Callender toured Australia with a new troupe, also named the Georgia Minstrels. In 1882, Hicks returned to managing the Callender's Georgia Minstrels. The words “Callender” and "Georgia" came to be synonymous with black minstrelsy, and the success of the Georgia Minstrels spawned numerous imitators. At the top of this broadside is a portrait of Callender described as ‘Manager.’ Below him are thirteen members of the troupe in suits, seated and holding a range of instruments: violins, viols, recorders, clarinets, tambourines, and other forms of percussion (if the number of members depicted here is a full representation, Hicks may still have been managing the troupe at this time, the description of Callender as ‘manager’ meaning something more like ‘owner’). Underneath the musicians, the phrase “Slave Troupe” is spelled-out in letters in the form of what appear to be bells of some sort (perhaps a musical element in their shows). The central scene in the bottom portion shows a slave-master on a horse and accompanied by a dog seemingly threatening a group of slaves picking cotton; a plantation house lies in the background; and a snake appears on a nearby branch. The image is flanked by a black man playing the banjo and a seated woman with a tambourine, both figures observing the plantation scene. A vignette in the lower left corner employs the trope of the happy, dancing slaves, while another on the right depicts two slaves sitting on a barrel and a chair with umbrellas, presumably depicting a scene from one of the troupe’s acts. The four corners feature decorative lettering, as well as emblems of music and theatre. In her essay, “The Georgia Minstrels: the Early Years,” Eileen Southern offers an illuminating overview of the troupe’s performances: “Like other black minstrel troupes in the 1860s, the Georgia Minstrels inherited from Ethiopian burnt-cork minstrelsy the standard practices that had been established in the 1840s and, along with this, negative stereotypical images of the black man. But there was enough flexibility in the standard procedures to allow for innovation and improvisation; from the beginning the Georgia Minstrels undertook to produce shows which were novel and distinctively ‘genuine,’ plantation black-American, and, at the same time, enough in conformity with minstrel traditions to please their interracial audience and keep them returning for more. … Contrary to widespread belief, the Georgia Minstrels did not draw heavily upon Negro folksong—at least not in its early years, if we are to judge from extant programs. Sam Lucas, the major songwriter of the troupe, specialized in ballads, ‘character songs,’ and comic songs. The other songwriters of the troupe, Jim Grace and Pete Devonear, wrote conventional minstrel or ‘plantation’ songs. All three, however, drew upon the slave songs as sources of refrain texts and melodics. Typically, the verse of the minstrel song was newly invented, the chorus drew upon or used a slave-song, and the piece concluded with an eight-or sixteen-measure dance chorus. Devonear's "Run Home, Levi" is representative; here, however, the borrowed material—from the slave song ‘I don't want to stay here no longer’—is used as a refrain rather than a chorus. The Georgia Minstrels frequently broke with tradition in regard to the kind of music they performed. … On such occasions as these, audiences were entertained with selections from the masters—Haydn, Verdi, Rossini—and with genuine Negro spirituals, such as had been popularized by the Fisk Jubilee Singers … [The troupe] successfully met the post-war public's insatiable hunger for entertainment and developed loyal followings among both black and white. For black entertainers—or ‘members of the profession,’ as they called themselves—the troupe functioned in a unique way: it was at once a haven for the established entertainer temporarily ‘at large’ and a training ground for the neophyte, who could serve his apprenticeship with some of the most eminent black artists of the times. … [the group] played an essential role in establishing the groundwork for a black musical theater.” Not in OCLC, nor does a google search locate other examples. In fact, google and OCLC searches yield just one other broadside advertising the Georgia Minstrels, held by the Library of Congress. A rare broadside advertising this important African-American minstrel troupe. REFERENCES: Dominique-René de Lerma. Hicks, (Charles) Barney at oxfordmusiconline.com; Southern, Eileen. “The Georgia Minstrels: the Early Years,” Inter-American Music Review (1989), pp. 157–167; Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up : The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), p. 199; Watkins, Mel. On the Real Side : Laughing, Lying, and Signifying—The Underground Tradition of African-American Humor that Transformed American Culture, from Slavery to Richard Pryor (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), p. 125. CONDITION: Soiled, mostly in the margins; reinstatement of several relatively small losses to image and border, a few repaired tears.

Item #6350

Sold